THE CUNARD - WHITE STAR LINER 'QUEEN ELIZABETH'

1938 - 1972

by John Shepherd

I joined the Cunard Line in March 1962 as an Assistant Purser and sailed on the QUEEN ELIZABETH throughout that year, before transferring to the Liverpool-based CARINTHIA in November, where I remained as Crew Purser for the next five years.

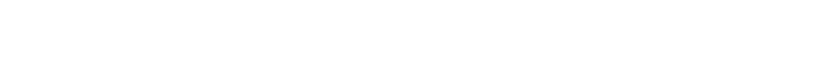

The QUEEN ELIZABETH of 1938 never visited the port of Liverpool, but on her stern were the words QUEEN ELIZABETH LIVERPOOL. That is quite sufficient to ensure her a place in the story of Liverpool ships.

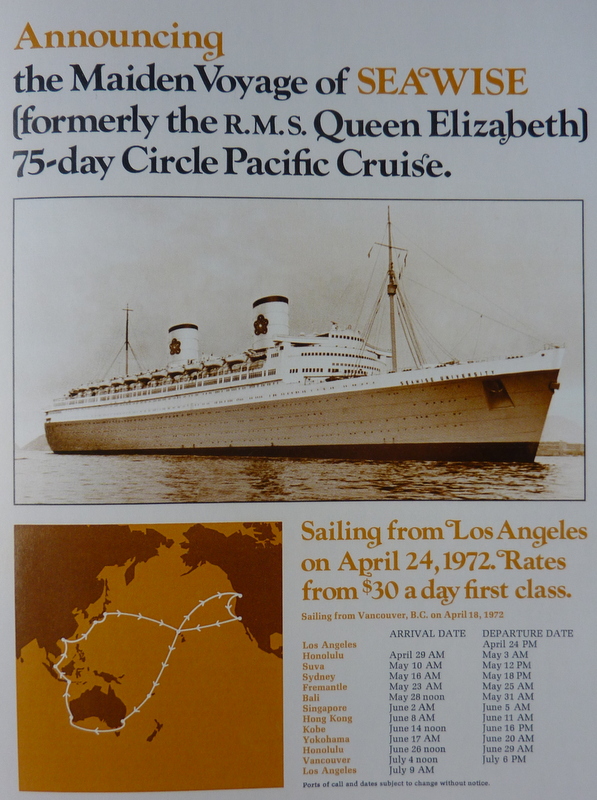

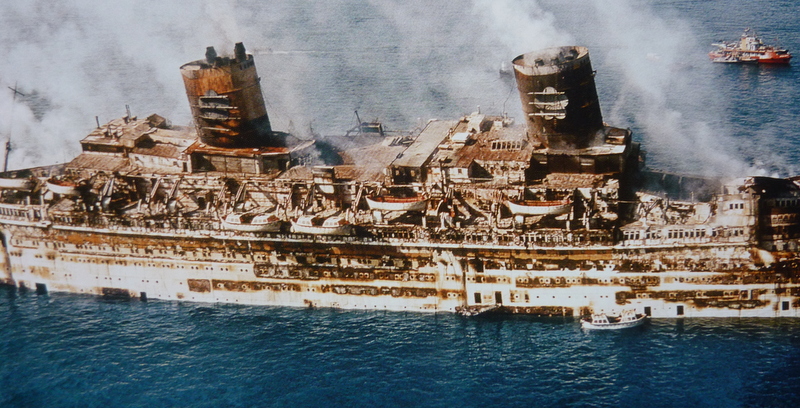

Over forty years ago, in 1972, the world's largest liner, the RMS QUEEN ELIZABETH, was lying on her side in Hong Kong harbour, a burnt-out hulk. This is the story of the ship from the planning stages of the late 1920s, her war operations, her amazingly successful passenger service of the late 1940s and 1950s, and her demise in the mid 1960s.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ I have recently uploaded three videos on to 'YouTube' about the QUEEN ELIZABETH. They are:

Cunard Line QUEEN ELIZABETH of 1938, Part 1 [30 minutes]

Cunard Line QUEEN ELIZABETH of 1938, Part 2 [30 minutes]

Arrivals & Departures Queen Elizabeth Southampton 1950 [20 minutes]

To view these, log on to 'You Tube', and enter into the search box the title of each video, exactly as I have shown it above. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ____________________________________________________

"The great solid block that is the headquarters of the Cunard Steamship Company stands on the Liverpool waterfront, beaten by the wind and the rain, bleached by the sun, facing the grey-brown waters of the River Mersey. This is, indeed, the very heart of a shipping city, where, standing in the windows of that building, one can see the ships of all nations passing by in procession at tide-time, almost as mundanely as the trams whose terminus is at the water's edge. Ferry boats fuss across the river, dodging between these ships, almost like children running across a busy road."

Cunard Building at Liverpool's Pier Head

When the above lines were written in the mid 1920s, the Cunard Line was operating its Southampton - New York express service with the MAURETANIA (1907), the AQUITANIA (1914) and the BERENGARIA (1913). The Company had replaced a number of its smaller ships, but there were no large replacements for the express service at the planning stage.

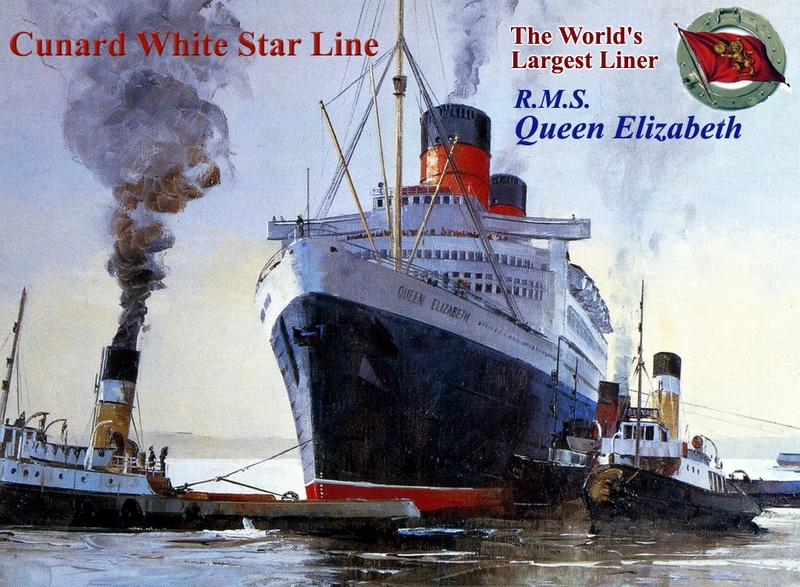

The QUEEN ELIZABETH approaching her berth at Pier 90 in the North River at New York in the late 1940s. (from an original painting by Robert Lloyd)

It was not until 1926 that Cunard began thinking about the replacements for the express steamers. The C.G.T. (the French Line) brought out the ILE DE FRANCE in that year, and it was known that it was planning to build a superliner (which would be the NORMANDIE). The Italians put the largest motor ship in the world, the AUGUSTUS, into service, and the White Star Line had laid down a new liner at Belfast. This would have been the OCEANIC, whose keel was laid at Harland & Wolff's yard in 1928. Because of the world depression, construction work had not gone very far before it was suspended.,

Following the First World War, Germany was building up her passenger fleet from 'scratch' in an era of new developments. In 1928 the Germans launched the BREMEN and the EUROPA. On her maiden voyage the BREMEN crossed from Cherbourg to the Ambrose Channel Light Vessel off New York at an average speed of 27.91 knots, smashing completely the MAURETANIA's proud record of twenty years standing.

On her maiden voyage in 1928, the German liner BREMEN captured the Blue Riband of the North Atlantic, crossing from the Bishop Rock to the Ambrose Channel Light Vessel off New York at 27.91 knots.

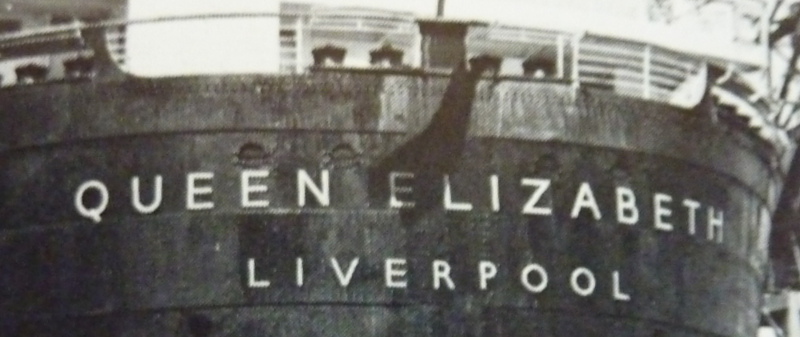

The BREMEN's triumphant return to Hamburg after her record-breaking crossing

It was against this background that the Cunard Company began the design stage for two new ships. They would follow the natural progression of developments then taking place in marine engineering and in naval architecture. Great steps forward were being made in both these fields. For the first time it seemed possible that two ships could be built which would be able to maintain a weekly express service between Southampton and New York, doing the work previously done by three ships.

The trend of development in the design of Atlantic liners since the coming of steam had been towards larger and faster ships; the larger ships being more comfortable as they were less affected by the elements, whilst the increased speed shortened the trip.

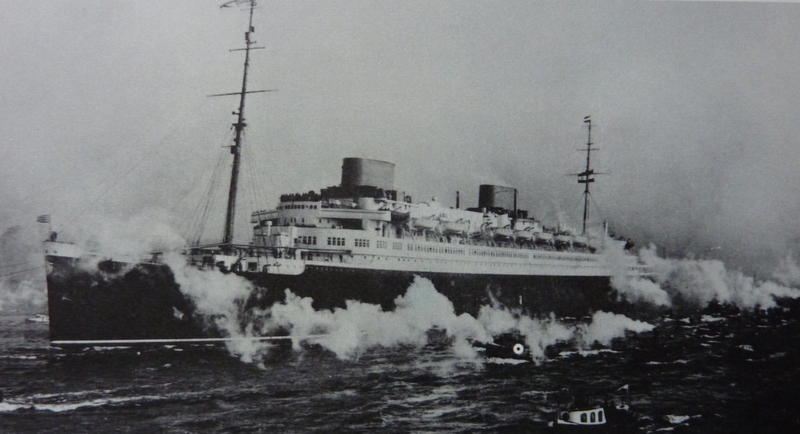

The QUEEN MARY photographed in mid-Atlantic from the QUEEN ELIZABETH's bridge

Experience had shown that once converted to oil burning, these ships could turn round in port in eighteen hours when necessary. It was reasoned, therefore, that if the passage time could be reduced to five days, it would be possible for two ships on a fortnightly service to do the work of three.

The distance to be covered in a year would be about 145,000 nautical miles. So it was clear that the ships must be fast, strongly built to face North Atlantic weather, and have a sufficient reserve of power to make up any time lost through bad weather. The ships would have to run without repairs for eleven months of the year. Reliable boilers would have to be chosen as there would be no opportunity for boiler cleaning in port.

The speed required for the 112-hour passage on the various tracks used across the Atlantic according to the season would be between 27.61 and 28.94 knots.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH off the Battery area of Manhattan as she sails up the Hudson (the North River) to her berth at Pier 90.

If oil were adopted as the best type of fuel, Cunard would always have to bear in mind the possibility of oil shortages, and back in 1926 it had been seriously suggested that the new ships might be generally arranged so that in the case of such an emergency arising it would be possible to convert them to coal burning.

The original design for the engines was for single-reduction geared turbines, the brainchild of Sir Charles Parsons, in which a reduction gear box is placed between the turbine and the propeller shaft for the purpose of allowing both the turbines and the propellers to run at speeds of revolution suitable for maximum efficiency; high speeds of revolution are required for turbine efficiency and low speeds for propeller efficiency.

The size of the two proposed superliners was not dictated in any way by a desire on the part of Cunard to have 'Big Ships' for their own sake. It was controlled simply by the necessity to provide sufficient passenger accommodation and propulsion to operate a two-ship weekly express service across the North Atlantic. Within that context, as Sir Percy Bates, the chairman of the Cunard Steamship Company, never tired of explaining: "The two new vessels represent the smallest and slowest ships which can fulfill these conditions and accomplish such a regular service."

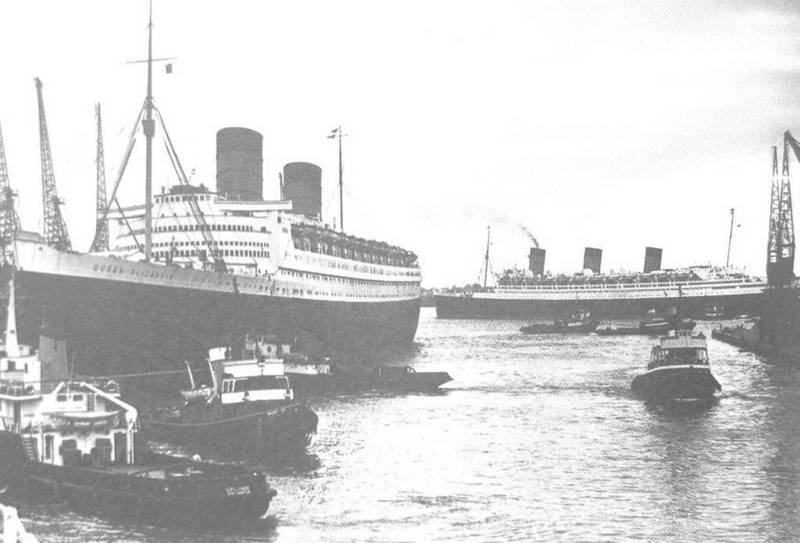

The QUEEN ELIZABETH docking on the north side of Cunard's Pier 90 in the North River, Manhattan. The two-funnelled MAURETANIA and the SYLVANIA are berthed at Pier 92. In the foreground are the United States Lines' UNITED STATES and AMERICA.

On 28th May 1930, the Cunard Company told John Brown & Company of Clydebank that it had been selected as the builder of the first of the two new ships. The keel of Yard No. 534 was laid on 27th December 1930.

A major problem to be settled concerned the insurance of the liner while she was being built, together with the future full sea risks when she was operational. The normal insurance market would not be able to provide cover for anything like the whole cost. Therefore Cunard approached the Government and asked them if they would bear the additional burden.

The outcome was the Cunard (Insurance) Act, passed in December 1930. This was designed so that the Government would assume responsibility of the risk of the ship's insurance value over and above the amount which the market could absorb. The value of '534' for insurance purposes during building was fixed at the full price payable by Cunard, namely £4 million. The market could only assume £2,700,000 of the risk.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH on her speed trials in the Firth of Clyde

In May 1930, Cunard began to make tentative enquiries about the possibility of dry-docking facilities at Southampton for its two new superliners. It was pointed out to the Southern Railway Company, the owners of Southampton Docks, that by 1933 a dry dock capable of taking a vessel 1,075 feet in length would be needed. The dock would have to be 124 feet wide at its entrance and have a minimum depth of 40 feet. The railway company expressed the view that the projected dry dock could not be started for some eight to ten years and that it would take between four and five years to complete. Sir Percy Bates told the Southern Railway that it was a question of 'no dry dock, no ship'.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH entering the King George V Dry Dock at Southampton which was specially constructed for the 'Queens'.

Following this ultimatum the Southern Railway decided to go ahead with the construction of a dry dock 1,200 feet in length, 135 feet wide and 48 feet deep, with a wide area outside the entrance for the ship to swing. The dock could be emptied of its 180,000 tons of water in four hours. On 26th July 1933, King George V and Queen Mary sailed into the new dock in the royal yacht VICTORIA AND ALBERT to perform the opening ceremony.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH alongside the quay at Cherbourg

Across the Channel at Cherbourg the French authorities had proved much more amenable. They went ahead with plans for new quay accommodation and worked amicably with Cunard officials. Cherbourg was chosen as the French port for the new ships as it had deeper water and a larger harbour than Le Havre. From the passengers' point of view it had the disadvantage of being 100 miles further away from Paris than Le Havre.

In January 1931 agreement was reached with the New York Port Authority for a thousand-foot long pier at a rent of £48,000 a year.

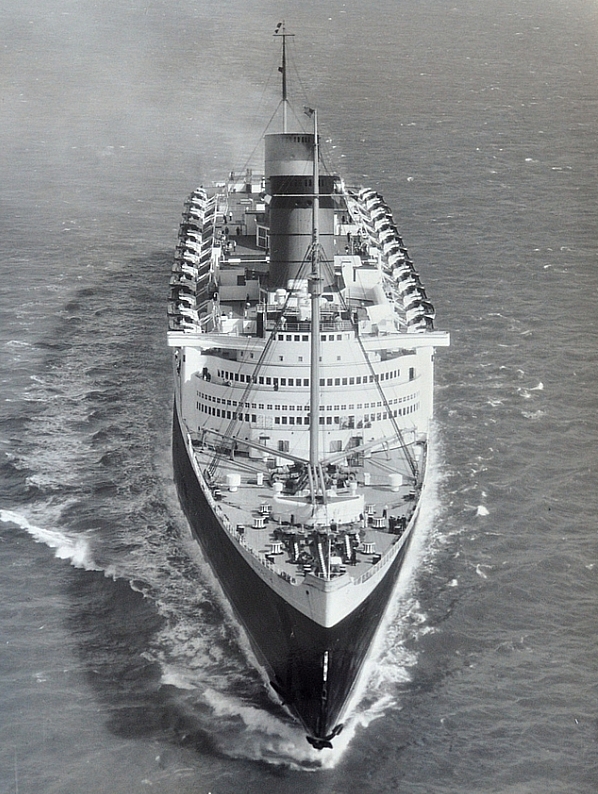

The QUEEN ELIZABETH at full speed in the North Atlantic

On Thursday 10th December 1931, the Directors of the Cunard Steamship Company gathered to look at the provisional figures for the year's trading For the first time for very many years the Company had not made a profit. The Directors were faced with the almost unbelievable fact that the gross revenue of the Company for the year was calculated to be nearly £2.5 million down on 1930.

The Directors decided that work must stop on No.534 - the QUEEN MARY - at noon on Friday 11th December 1931.

A painting by Captain Stephen J Card of the two 'Queens' passing in mid-Atlantic. As Sir Percy Bates was fond of saying: "These two new vessels represent the smallest and slowest ships which can economically maintain a two-ship weekly trans-Atlantic service."

Neville Chamberlain, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was convinced that faced with the growing competition from foreign liner companies there was not room for two big British companies acting in opposition to each other on the North Atlantic trade. He wrote in his private diary: "My own airm has always been to use '534' as a lever for bringing about a merger between the Cunard and White Star Lines, thus establishing one strong British company in the North Atlantic trade."

It was Chamberlain's firm belief that the British Government should guarantee a building loan to the Cunard Company on the condition that the two companies merged into one united front against the foreign competition. The Cunard policy of the two-ship express service was thoroughly sound and at the same time economic. Cunard's finances were in a very strong state whilst those of White Star were very poor. Chamberlain was also convinced of the tremendous importance from a prestige point of view of new large British ships steaming into New York harbour.

It was proposed that the Cunard Steamship Company and the Oceanic Steamship Company (the White Star Line) would both sell their North Atlantic fleets and assets, including '534', to a new company to be called Cunard - White Star Limited. The Government then proposed to lend the new company £9.5 million which would be divided into three portions:

+ £3 million to complete '534' + £1.5 million working capital + £5 million for a furture sister ship - the QUEEN ELIZABETH

Neville Chamberlain now had the difficult task of steering the North Atlantic Shipping (Advances) Bill through the tortuous channels of Parliament. Eventually both the House of Commons and the House of Lords voted and the Bill was passed on 27th March 1934. One week later work resumed on '534'. The QUEEN MARY (as '534' became after all the secrecy) was launched nearly six months later on 26th September 1934.

Under the terms of the Cunard Insurance Act, Cunard was obliged to start work on the second ship before the Act expired in 1936. From the outset the intention had been to operate a two-ship service on the North Atlantic. On 25th November 1935 Sir Percy Bates wrote to Swan Hunter; Vickers Armstrong; John Brown and Cammell Laird advising them that, although his Board had not reached any final decision, they might decide to build a vessel to run alongside the QUEEN MARY. With White Star now under Cunard's wing, Harland & Wolff at Belfast were also invited to tender, a position not previously open to them.

In writing to Cammell Laird, Sir Percy said that he was not entirely confident that it could deal with such a large ship and that in particular they might not be able to move the ship into their fitting-out basin. Harland & Wolff found itself in a peculiar situation. The wording of the Cunard Insurance Act specified 'the construction of two vessels in Great Britain', which precluded the Belfast yard from tendering as Belfast, although in the UK, was not in Great Britain.

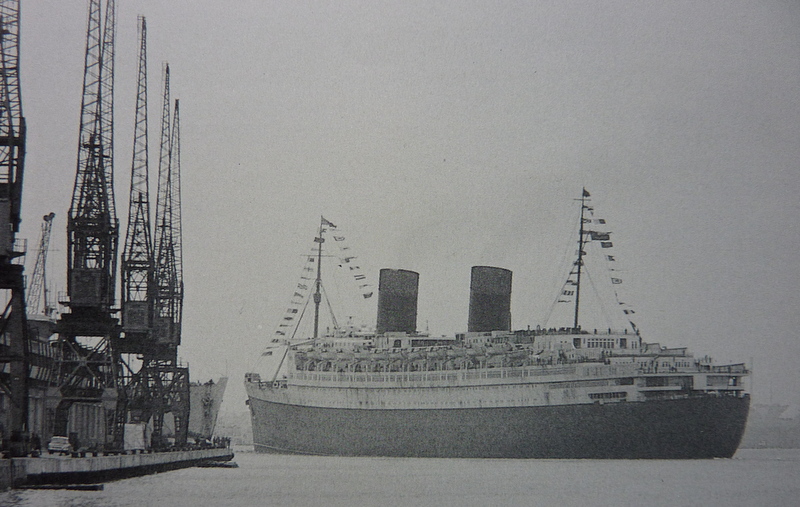

The QUEEN ELIZABETH sailing from Southampton

In May 1936 tenders were opened from John Brown, Cammell Laird, Vickers Armstrong and Swan Hunter. The Clydebank yard was awarded the contract with a tender of £4,293,000. The Cammell Laird tender had been £4,683,000. On 27th May the Clydebank men were told they had the order.

Towards the end of June 1936, in reply to a question in the House of Commons, the Chancellor Neville Chamberlain said: "I have received a request from the Cunard - White Star Company for authority to use the sum available under the North Atlantic Shipping (Advances) Act for the construction of a second ship ....... I have agreed in principle." The £5 million was released on 28th July.

Early in July 1936 Stephen Piggot (the managing director of John Brown) wrote to Sir Percy Bates saying that Yard No.535 had been reserved for the new ship. (The QUEEN MARY had been ship number 534). On 11th July Bates replied asking Piggot to 'think of another good number'. The reason was the Chancellor of the Exchequer's apprehension at what might be asked of him by his critics when making the announcement of the order in the House, namely 'that this tender business was all a farce, and that the order was in Brown's pocket from the start.'

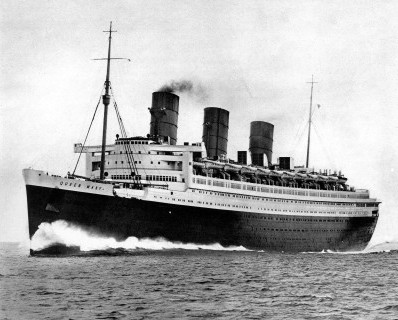

Sir Percy Bates stressed that the new QUEEN ELIZABETH 'would be no slavish copy of her sister, the QUEEN MARY' In this photograph the QUEEN MARY is undertaking her speed and acceptance trials over the Arran Mile, in the Firth of Clyde.

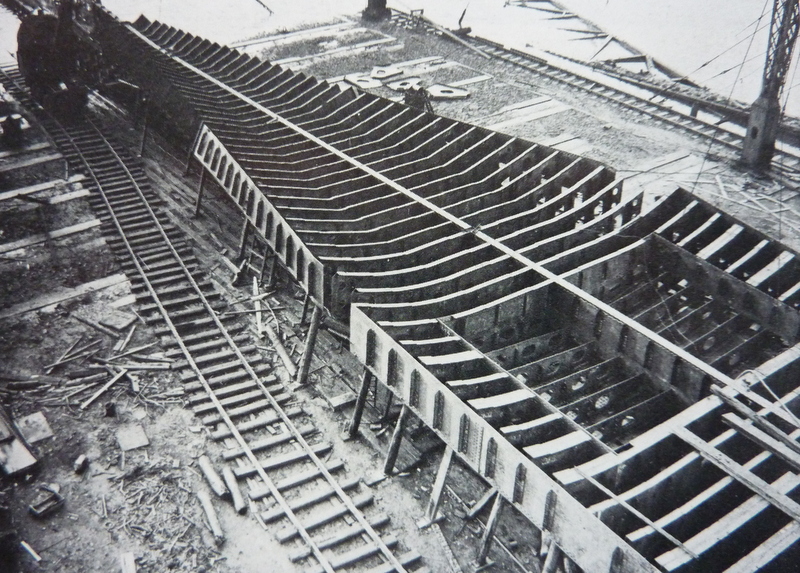

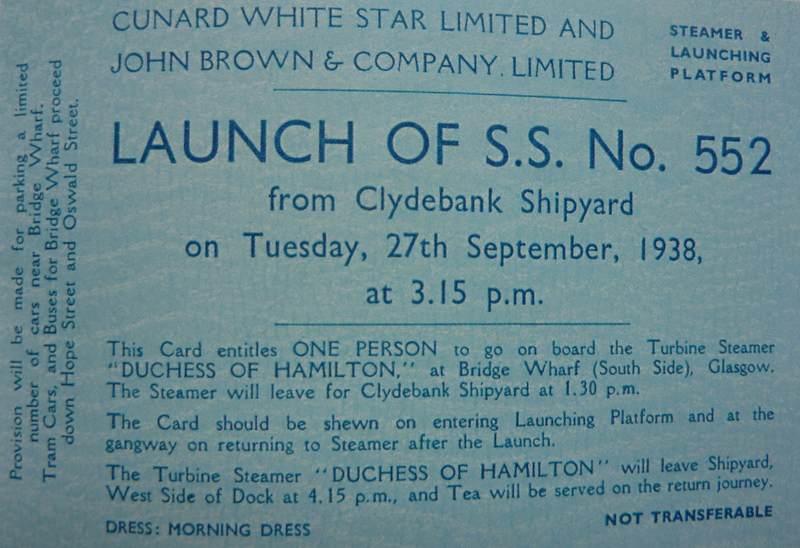

The contract was signed on 6th October 1936 and the keel of ship number 552 was laid on 4th December. Work on the QUEEN ELIZABETH proceeded rapidly and by February 1937 Colvilles were supplying steel to Clydebank for this ship at the rate of 500 tons a week.

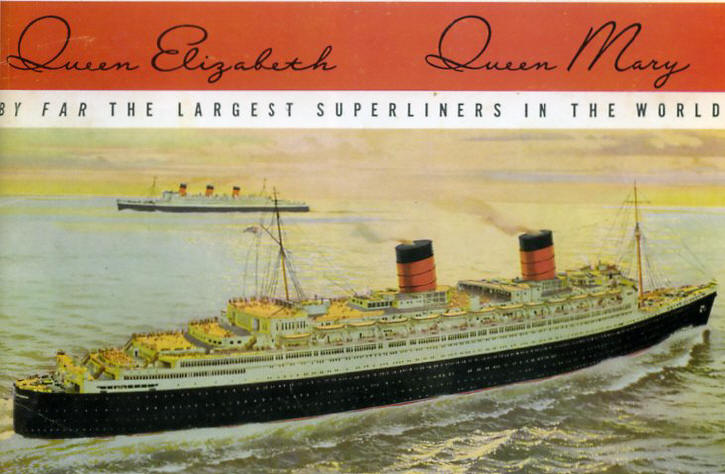

Cunard was determined that the new ship would be based on the latest revolutionary developments that had taken place in naval architecture and marine engineering. Sir Percy Bates stressed that "she would be no slavish copy of her sister". The QUEEN MARY's arch rival on the North Atlantic - the French Line's superb NORMANDIE - was studied in detail.

The NORMANDIE - the QUEEN MARY's arch rival on the North Atlantic, seen here at anchor at Spithead

The NORMANDIE had one edge on the QUEEN MARY in being aesthetically more pleasing through her revolutionary streamlining and lack of visible deck 'clutter'. Costing almost twice as much as the Mary, the French liner was also more lavish in her first-class apartments.

Sir Percy Bates had wisely waited for anticipated developments in boiler design to occur. As a result only twelve boilers were needed for the QUEEN ELIZABETH, rather than the twenty-four in the Mary. Just two funnels were needed on the new ship instead of the three on the Mary and these were self-supporting, having their stays on the inside of the stack. The prominent square ventilation cowls on the Mary were also dispensed with on the new ship; fans of a newer design were installed inside the ship.

Another obvious difference between the two ships was the lack of a forward well deck on the new QUEEN ELIZABETH. This had been included on the Mary to spend the force of any heavy sea that might break over the bow before the water could damage the superstructure. This anticipated event never occurred and was considered very unlikely to occur, so the well space was plated in and used for additional accommodation.

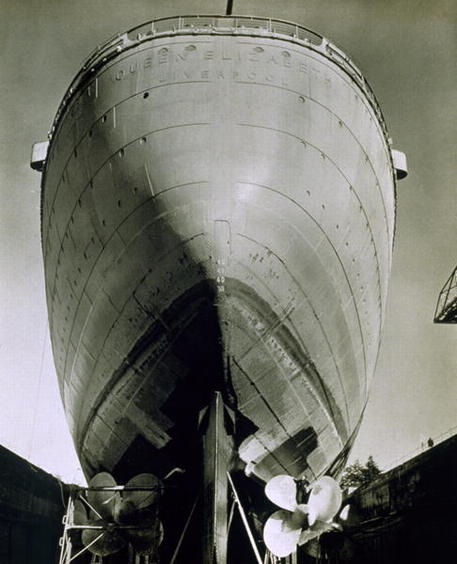

The QUEEN ELIZABETH had a heavily raked bow

The QUEEN ELIZABETH's bow, unlike that of the Mary, was heavily raked. This enabled a third anchor, the bower, to be carried allowing the anchr to fall well clear of the stem. This rake also gave the Elizabeth a longer overall length: 1,031 feet as against the 1,019 feet of the QUEEN MARY.

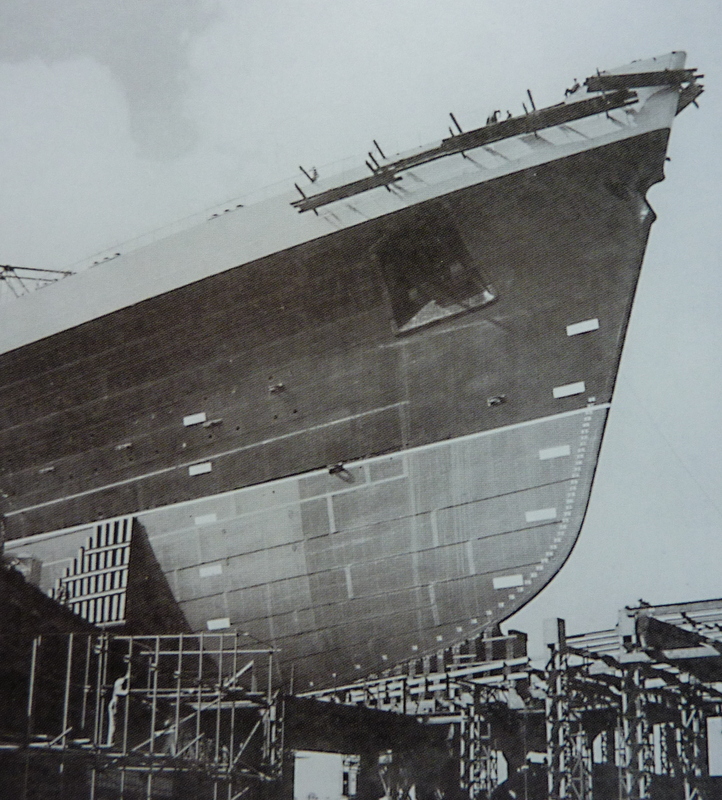

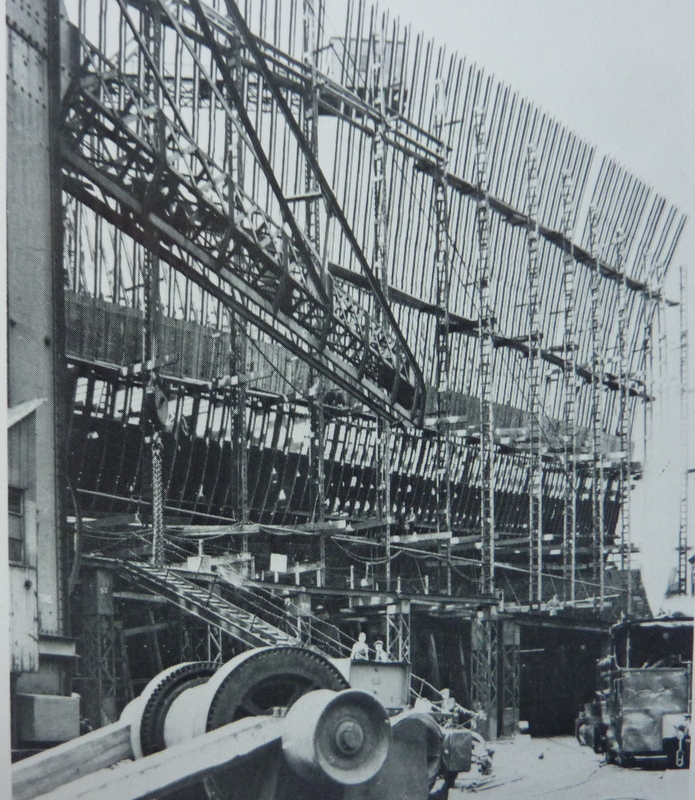

The new ship was constructed on No.4 slipway by using 5-ton derrick cranes and a 10-ton tower crane. Heavy castings were erected by using derrick poles or sheer legs. Steam locomotives delivered the steel plates, but lighter items were brought in by horse-drawn lorries.

Construction work on the QUEEN ELIZABETH

To ensure that good progress was maintained during construction, the General and Shipyard Managers met all the departmental head foremen at the gangway every Friday. This 'Glee Party', as it was known, then toured the vessel deck by deck. Any problems that were encountered were resolved by the foremen concerned by sending in extra men to assist temporarily with the work that had fallen behind and bring the construction work back to its timetable. A skilled craftsman working on the QUEEN ELIZABETH earned just £3.2s.0d for a 47-hour work.

As an indication of the worsening European situation, the keel of the Royal Navy's newest battleship, HMS DUKE OF YORK, was laid on 5th May 1937 on the slipway adjoining the QUEEN ELIZABETH.

The view from the top of the shipyard crane of the QUEEN ELIZABETH's bridge and foredeck.

As a triumphant fanfare to the launch of the QUEEN ELIZABETH, the Mary captured the Blue Riband in August 1938 with a speed of 31.69 knots, a record that would stand for fourteen years. Cunard always refused to acknowledge the recently introduced Hales Trophy as a tangible symbol of the achievement.

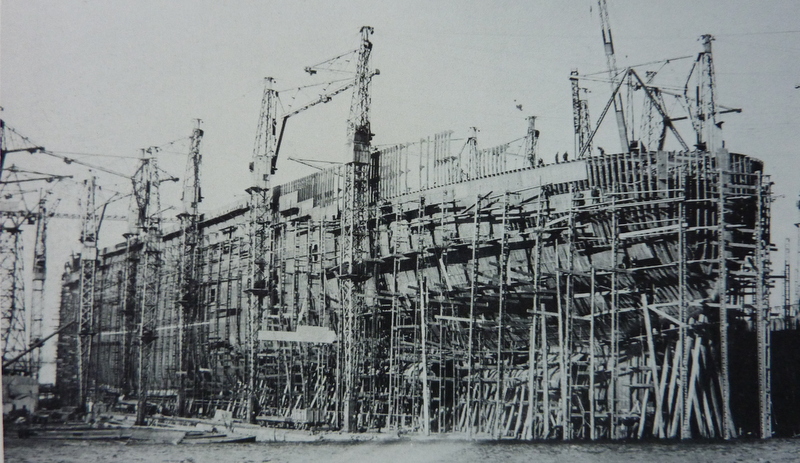

The QUEEN ELIZABETH almost ready for launching

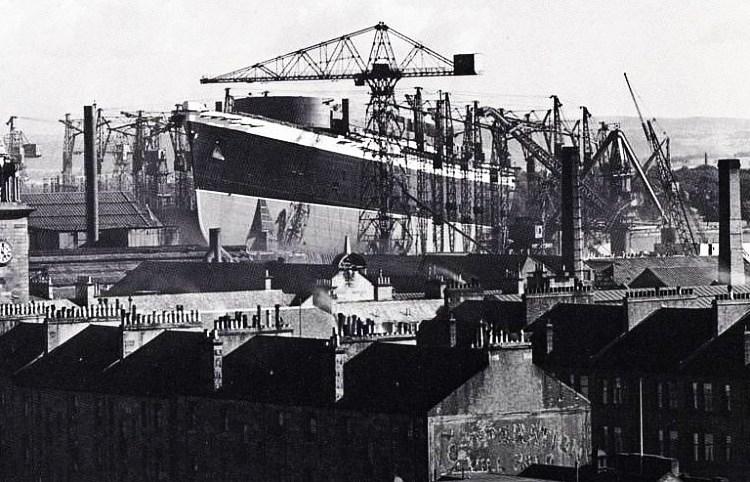

The QUEEN ELIZABETH towers over the tenements of Clydebank

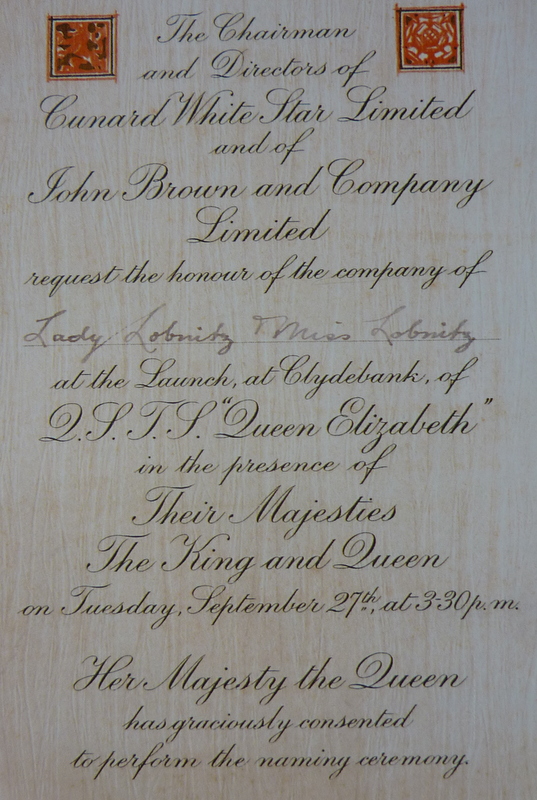

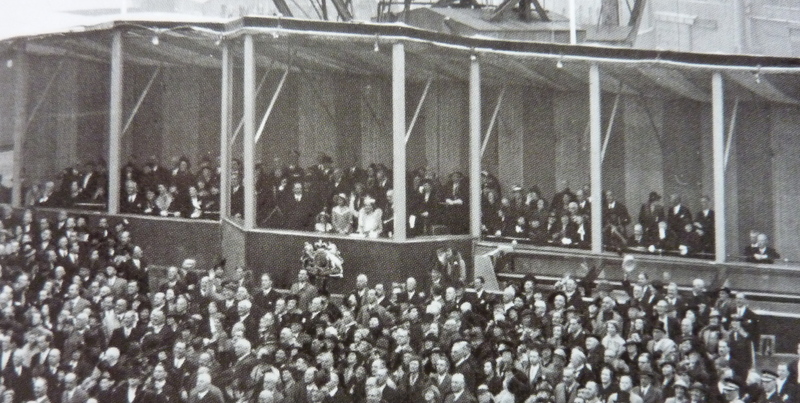

Four years and one day after the launch of the QUEEN MARY, on Tuesday 27th September 1938, Queen Elizabeth, who was Queen Mary's daughter-in-law, consort of her son King George VI, stood at the head of the same slipway on which the QUEEN MARY had been built. She was there to launch the second of Cunard's superliners - the QUEEN ELIZABETH.

King George VI had remained in London at the request of the Prime Minister. War seemed very much to be a likelihood on that September day, but the King had sent a message which Queen Elizabeth incorporated into her speech. However, the launching ceremony, which was being broadcast to the nation by radio, did not go without incident.

As the moment arrived for the launch, the QUEEN ELIZABETH was delicately balanced on her slipway and for many hours previously, because of the removal of most of the supporting timbers, an almost imperceptible movement had already taken place. The new liner had a weight on the slipway of 39,400 tons. After the formal speeches had been completed there was a pause as high tide and slack water were awaited. Suddenly there was a crash of breaking timbers and No.552, on her own volition, started on her un-named journey towards the Clyde.

Queen Elizabeth launches the QUEEN ELIZABETH

Queen Elizabeth with Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret, accompanied by Sir Percy Bates, the Cunard chairman, on the launching platform

At around this time the Queen's microphone failed but with great presence of mind, Her Majesty quietly and almost unheard by those around her said: "I name this ship QUEEN ELIZABETH and wish success to all who sail in her." Then, with the same pair of gold scissors that Queen Mary had used to perform the launching ceremony of her namesake, she cut the red, white and blue ribbon which released the bottle of Empire wine to break, just in time, against the new ship's accelerating bow.

Archive British Pathe film footage of the launch can be viewed by logging on to:

< British Pathe The Queen launches the QUEEN ELIZABETH 1938 >

The QUEEN ELIZABETH enters the waters of the River Clyde

The crowds at John Brown's shipyard at the launch of the QUEEN ELIZABETH

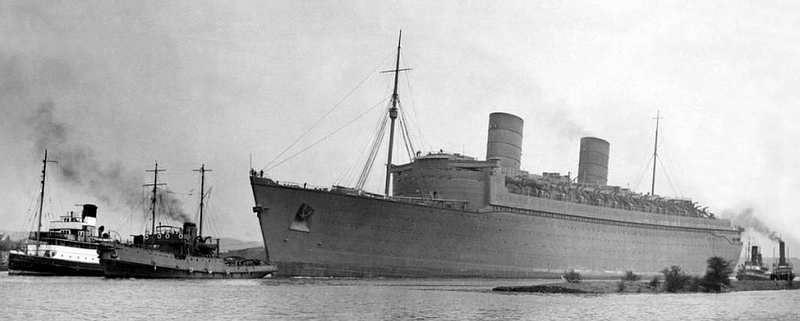

The QUEEN ELIZABETH is towed round to the fitting-out basin at John Brown's shipyard, following her successful launch

The QUEEN ELIZABETH was the culmination of Sir Percy Bates' own initiative; the fulfilment of a long-cherished dream held by many shipowners; that a weekly trans-Atlantic ferry service should be maintained by two ships rather than by three, or even four (sometimes mismatched) vessels that had previously - and expensively - been required.

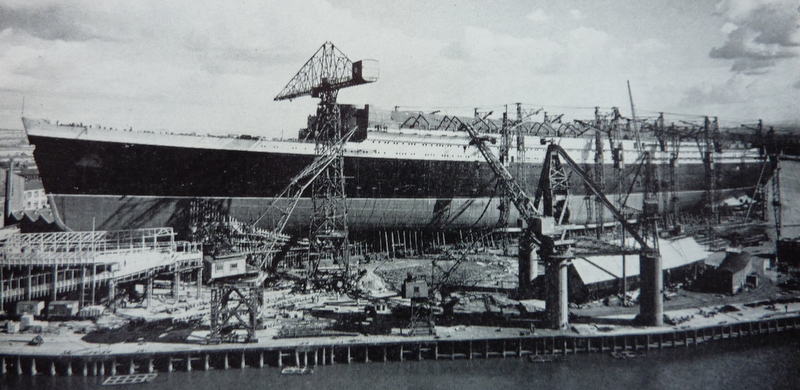

After her launch the QUEEN ELIZABETH was towed round to the fitting-out berth where she would remain for the next sixteen months. A barrier was then constructed around the hull to shut her off from the river and to prevent the Clyde-borne silt building up around and under the hull. For almosr five years John Brown & Company had carried on a correspondence with the Clyde Navigation Trust dealing with the safe navigation of the liner on her one and only journey to the open sea. This would involve a great deal of dredging and the removal of rock outcrops that might hazard the ship's safe progress. The river was also widened in places, especially at Dalmuir where the QUEEN MARY had grounded for many anxious seconds as she proceeded to the Tail of the Bank.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH at the fitting-out berth at John Brown's shipyard

As 1939 wore on, men and materials were taken away from the liner as Admiralty work took priority, and the pace of work on board slowed down.

When considering the comfort of those on board, Cunard had decided against the installation of stabilisers. 'The Times' in its special Cunard - White Star Supplement of 27th September 1938 (the date of the Elizabeth's launch) said that: 'no practicable installation of this type [gyro stabilisers] could possibly be of the slightest use in vessels the size of the QUEEN MARY and QUEEN ELIZABETH ...... to date the safest and easiest crossings are secured by sheer size, coupled with good form design, bilge keels of practicable dimensions and careful experienced seamanship. The stability of the QUEEN MARY has proved ample at all times to make the ship as safe and comfortable as it is possible for any vessel to be when passing through an Atlantic storm.' The truth was rather different, as the QUEEN MARY had a long, ponderous roll in a heavy beam sea which was only cured by the installation of two sets of Denny-Brown stabilisers in the late 1950s.

On 22nd August 1939 it was announced that the maiden voyage of the QUEEN ELIZABETH was scheduled to leave Southampton on 24th April 1940. However, war was declared just twelve days later.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH leaving Clydebank on 26th February 1940

Undoubtedly the incomplete QUEEN ELIZABETH was the greatest dilemma facing John Brown's on the outbreak of war. The ship sat like a giant beacon in the middle of Clydebank, visible for miles around. There was now no hope of her entering service as the jewel of the British merchant marine. During the first weekend of the war her newly erected forward funnel, resplendent in Cunard red and black, was hastily overpainted in grey. At first it was proposed that work on the Elizabeth would gradually be brought to a standstill as men transferred to warship work. Sir Percy Bates, dismayed at this prospect, wrote to the Chief of Naval Staff, Rear Admiral Burrough, for a decision on the ship's future.

Questions were soon asked in Parliament as to what possible use the two Cunard leviathans could be in wartime. Suggestions ranged from laying up the Elizabeth in a sheltered Scottish loch to selling her to the Americans. The two ships' real potential had yet to be appreciated. Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, expressed his fears for the safety of the QUEEN ELIZABETH and felt that she would fall victim to Nazi bombers in her exposed site at Clydebank. On 6th February 1940 he ordered that the liner should leave the Clyde at the earliest possible date and 'remain away from the British Isles for as long as this order remains in force'. This would also free the fitting-out berth which was urgently needed for the DUKE OF YORK.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH leaving the fitting-out berth at John Brown's shipyard, bound for the Tail of the Bank off Greenock.

The QUEEN MARY had left Southampton on 30th August 1939 on a liner voyage to New York with 2,328 passengers and remained there after her safe arrival, lying alongside Cunard's Pier 90.

The Clyde Navigation Trust indicated that the dredged channel in the Clyde would not be ready before the end of February 1940. In that year there would be only two days on which a high enough tide would be available to move the QUEEN ELIZABETH. The first day was Monday 26th February and just after noon, escorted by six tugs, the new ship left the fitting-out basin at Clydebank and proceeded down the River Clyde to an anchorage at the Tail of the Bank. It took about an hour to manoeuvre the ship's head downstream towards the sea and gradually a crowd of several hundred gathered to watch the QUEEN ELIZABETH slip quietly, almost furtively, by. To many, her appearance must have come as a bit of a surprise for no longer was she in pristine Cunard paintwork of black hull and white superstructure, but she had been completely repainted in dull uniform Admiralty grey.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH slips away from John Brown's shipyard at Clydebank on 26th February 1940

The QUEEN ELIZABETH had also been fitted with four miles of rubber coated copper cable would around her enormous hull. This was known as a 'degaussing' coil. It was named after Dr Gauss, a nineteenth century expert on magnetism, whose theories had enabled the Germans to produce their new lethal magnetic mines. The object of fitting the coil (one of the first to be so fitted) was hopefully to render the ship immune from magnetic mines by neutralising the ship's magnetic field.

The following afternoon, Tuesday 27th February, the QUEEN ELIZABETH was officially handed over to Cunard - White Star at 3.pm as she lay at anchor at the Tail of the Bank - untested and untried. Over the next three days the ship took on eighteen of her twenty-six lifeboats. These had been floated down the Clyde in order to reduce the liner's weight and thus reduce her draught during that short critical journey.

Just over 400 crew (mostly from the AQUITANIA) had joined the QUEEN ELIZABETH at Clydebank, under the command of Captain Jack Townley, signing Articles for a short coastwise voyage which would ostensibly terminate at Southampton where a hurriedly prepared dry-docking plan had been received by the port authority.

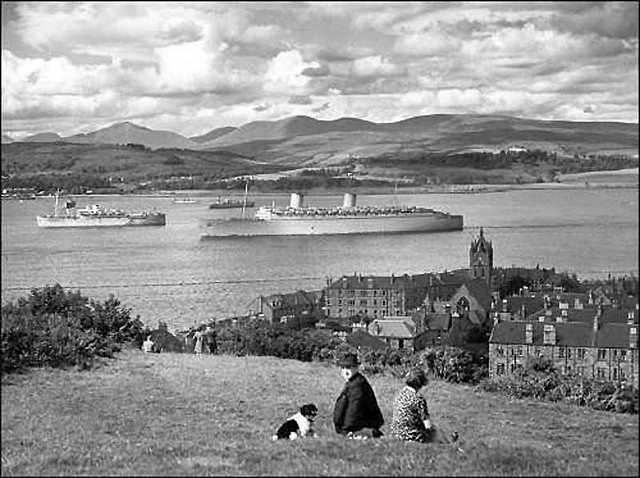

The QUEEN ELIZABETH at the anchorage at the Tail of the Bank off Gourock in the Firth of Clyde

At a boat drill on 27th February the assembled crew were told of Churchill's order that the ship was to leave British waters. This meant that the crew had to re-sign on foreign-going Articles. They demanded £50 per man danger money-cum-bonus, but were given £30 plus £5 per month extra pay. Those crew members who, for family or other reasons, declined to sign the new articles were taken off the QUEEN ELIZABETH, sworn to secrecy and subsequently spent many hours, virtually interned, on board the Southampton tender ROMSEY in a nearby loch. Not until the Elizabeth had sailed on 2nd March 1940 was it considered safe to release them.

Steam was raised on all boilers on 1st March. The King's Messenger was awaited as he would bring the order to sail. He arrived at seven in the morning on Saturday 2nd March 1940 with sealed orders which were only to be opened when the QUEEN ELIZABETH was out at sea. The new ship weighed her bower anchor half an hour later and with a mean draught of 37 feet 9 inches slipped through the anti-submarine boom that stretched across the Clyde between the Gantock Rocks and the Cloch Lighthouse at 8.15am. Over a two-hour period engine revolutions were increased from 100 (17 knots) to 154 (26 knots). When a speed of 25 knots had been reached and maintained for one hour, the escorting warships were informed that the 'engine trials' had been satisfactory and that there was no objection to their standing down. At eleven o'clock that evening Captain Townley opened his sealed orders and the Elizabeth's destination was at last known - New York.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH sets off on her 'secret' dash to New York

Captain Duncan Cameron, the Southampton pilot, was still on board. Cunard had insisted that he sail with the ship on her supposed coastal voyage as part of a ruse to throw enemy agents off the scent as to her actual destination.

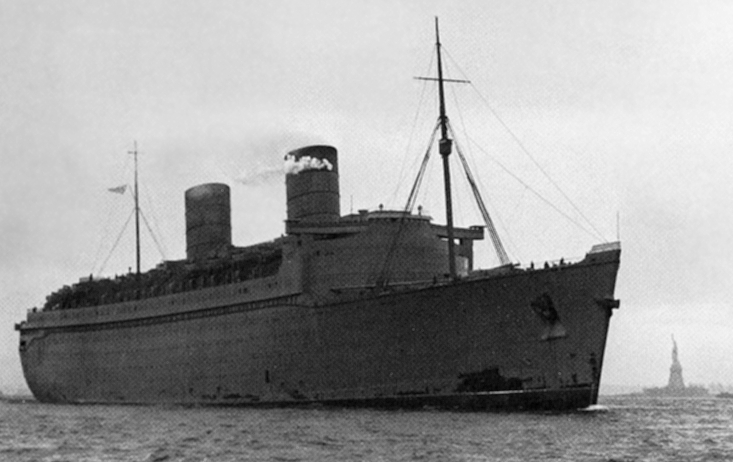

The QUEEN ELIZABETH passing the Statue of Liberty, New York, on 7th March 1940 on the completion of her successful 'secret' dash across the North Atlantic.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH arrives at New York on 7th March 1940

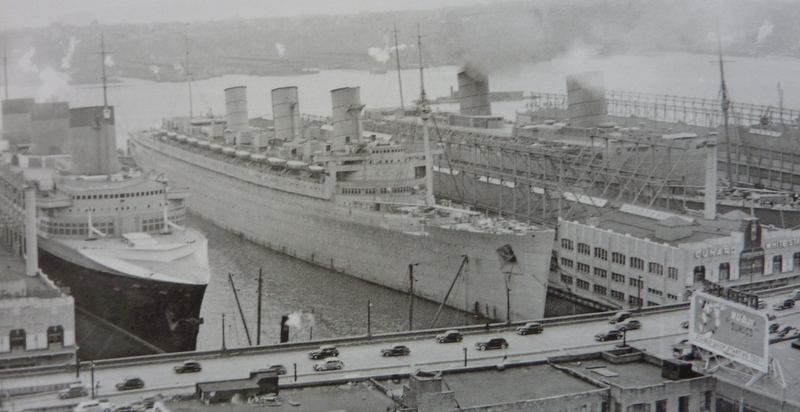

The QUEEN ELIZABETH approaching the north side of Pier 90 at New York. In the centre, on the south side of Pier 90, is the QUEEN MARY, and across the dock from her, on the north side of Pier 88, is the NORMANDIE.

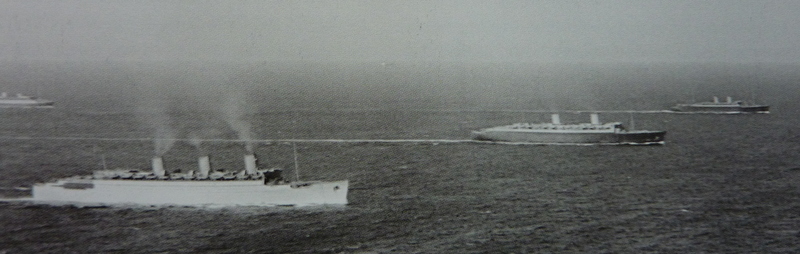

Top to bottom: the MAURETANIA, the NORMANDIE, the QUEEN MARY and the QUEEN ELIZABETH together at New York on 10th March 1940.

Five days, nine hours and 3,127 nautical miles after leaving the Tail of the Bank, the QUEEN ELIZABETH passed the Ambrose Channel Light Vessel off New York and picked up her pilot. She docked on the north side of Pier 90 at 5.pm on the afternoon of Thursday, 7th March 1940. Both Queen Elizabeth and Churchill sent messages of congratulation to Captain Townley. The QUEEN MARY was berthed on the south side of Pier 90, and on the north side of Pier 88 lay the French Line's NORMANDIE. The world's three largest liners were together for the first and, as events were to prove, the last time.

For just fourteen days between 7th and 21st March 1940, the world's three largest liners were together at New York. They are (left to right) the NORMANDIE, the QUEEN MARY and the QUEEN ELIZABETH.

A fortnight later, on 21st March 1940, the QUEEN MARY slipped quietly away: her work as a troop transport was about to begin.

The majority of the QUEEN ELIZABETH's crew left for home on Cunard's SCYTHIA, leaving just 143 men to form a skeleton crew. On the orders of the neutral American government (in accordance with the Geneva Convention), only maintenance or construction work of a non-beligerent nature could be carried out on the liners moored along the New York waterfront. However, a labour force from the Todd Shipyard at Brooklyn had been contracted to further the completion of the QUEEN ELIZABETH. Wooden decks had to caulked and electric cables connected.

Towards the end of 1940 additional seamen arrived on board the QUEEN ELIZABETH, having travelled from Halifax, N.S. The ship's company was brought up to 465 and at 3.30pm on 13th November 1940 the Elizabeth, heavily laden with fuel and water, slipped away from New York and headed south.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH had now been in the water for over two years since her launch on 27th September 1938. She urgently needed to be drydocked to have the remains of her launch gear removed from her bottom plates which would then have to be cleaned and painted. There were only five dry docks in the world which could accommodate the Elizabeth. The King George V Dock at Southampton, specially built for the 'Queens' was unusable because it was within range of Nazi bombers; the use of the American dock at Bayonne, New Jersey, was denied because of U.S. neutrality; the Esquimault dock on the west coast of Canada was just too far away, and the French dock at St Nazaire (built for the NORMANDIE) was out of the question.

This left only Singapore and the QUEEN ELIZABETH would have to make two stops to take on fuel and water on her voyage from New York. She had been designed for five-day transatlantic passages, not for long voyages. The first stop was at Trinidad where she rendezvoused with a tanker five miles off Port of Spain. After that she sailed to the British naval base at Simonstown, to the south of Cape Town.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH arrived at Singapore three weeks after leaving New York for a seven-week conversion into a troopship with accommodation for 5,000 troops. Whilst in Singapore many of the crew frequented a pub called the 'Pig and Whistle'. The name of this establishment so caught their fancy that the crew bars on all Cunard liners were subsequently named in its honour.

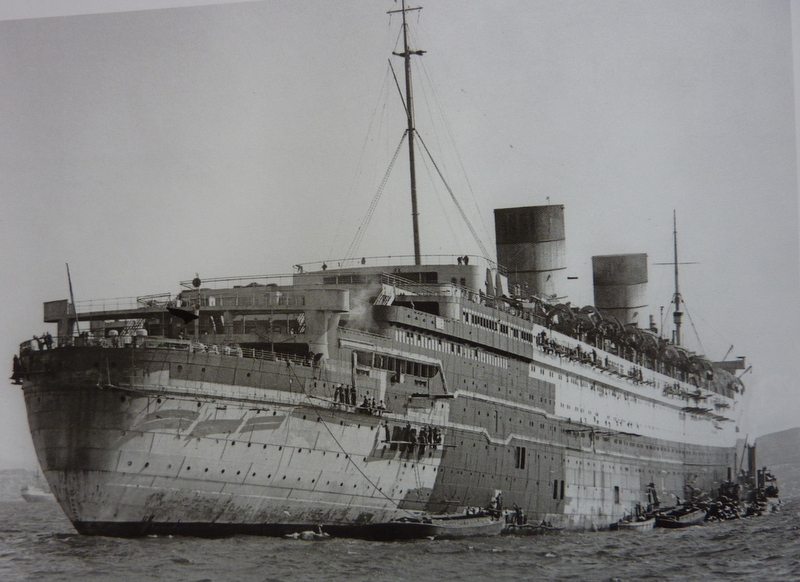

The QUEEN ELIZABETH at anchor in Sydney Harbour waiting to embark 5,000 troops on a northbound convoy to Suez.

After leaving Singapore the QUEEN ELIZABETH headed for Sydney. More than a year after the two 'Queens' had last met in New York, they sailed in company for the very first time in April 1941. The Elizabeth carried 5,600 Australian troops to bolster the defences of Egypt against the enemy's incursions into North Africa. Although the 'Queens' could easily manage 27 or 28 knots, they were reduced to the convoy's common speed of around 20 knots. On the return southbound voyages the ships carried Allied wounded, internees or enemy prisoners-of-war, stopping off at Ceylon.

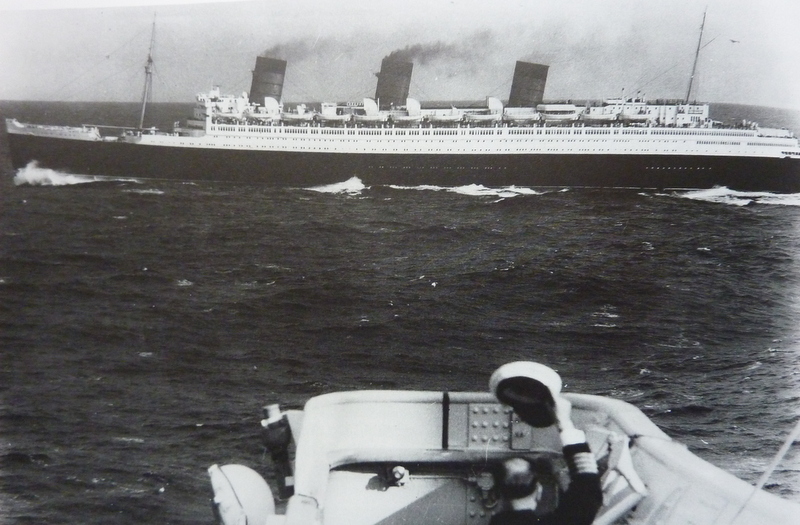

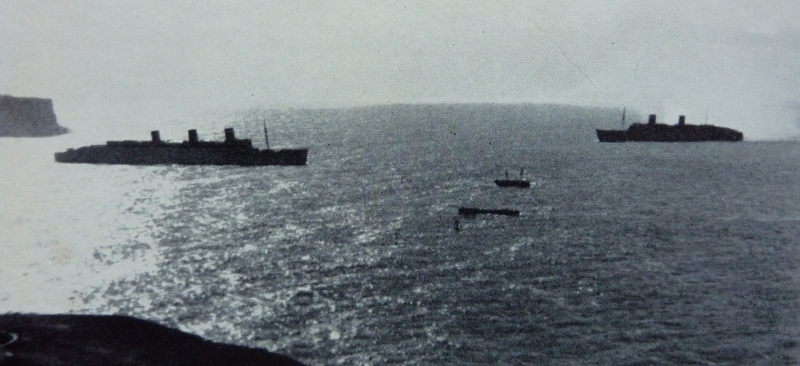

The first meeting of the two 'Queens' at sea - off Sydney Heads in 1941

Security was paramount at all times, but one particular breach was recalled by Dr Maguire, the surgeon on the QUEEN ELIZABETH. It occurred one day out of Ceylon and Dr Maguire remembered waking suddenly because the engines were slowing down. He went on deck and saw three great ships - the two 'Queens' and the ILE DE FRANCE stationary. They were huge sitting targets in a hostile ocean. The cruiser HMAS CANBERRA had lowered a pinnace which was cruising calmly around collecting bags of mail from each. Dr Maguire recalled that the cruiser HMAS SYDNEY had been sunk by the German KORMORAN without a single survivor only a few days before, not far from the present position. Dr Maguire said that he never did find out just who was responsible for that risky mid-ocean mail collecting. It was certainly the last time that the two 'Queens' ever stopped at sea in war time.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH (centre) and the QUEEN MARY (left) sail through the Bass Strait in convoy

With Japan and the United States entering the war after the debacle of Pearl Harbor on 7th December 1941, the QUEEN ELIZABETH was laid up at Sydney for seven weeks. The Pacific was too dangerous for her with both German and Japanese submarines on the prowl. The Australians also needed what was left of their depleted army for their country's own defence in case of Japanese invasion.

It was eventually decided to send the QUEEN ELIZABETH to Canada for drydocking at Esquimalt. (The Singapore facility was no longer available). A large amount of tropical growth that was fouling the liner's bottom plates needed to be removed: it was estimated that the growth reduced her speed by two knots or more. Two stops would be required for refuelling and watering. The first was New Zealand and the second was Nuku Hiva in the Marquesas Group of islands.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH in dry dock at Esquimalt, Vancouver Island, BC.

After Esquimalt the QUEEN ELIZABETH sailed for San Francisco, and, on arrival, briefly ran aground near the Golden Gate Bridge. During a conference on board, the U.S. military was told how many men had been transported on each Sydney - Suez voyage. The Americans were characteristically amazed and within five days had removed the Australian hammocks and bunks, and in their place had fitted fold-down 'Standee' beds, made of tubular steel and easy to clean canvas webbing. These were installed two, three and five to a tier in every available space and the QUEEN ELIZABETH left San Francisco in a small convoy bound for Sydney with eight thousand troops on board which were needed to bolster Australia's depleted forces until some of her own troops could be recalled from the Middle East.

Cabins designed for two passengers were equipped with 'Standee' bunks and accommodated up to eight G.I.s.

After disembarking the U.S. troops at Sydney on 6th April 1942, the QUEEN ELIZABETH remained in port for thirteen days before sailing for Fremantle on 19th April. From there she sailed to Simonstown (Cape Town) where German prisoners of war boarded, heading for internment in the United States. After a call at Rio de Janeiro, the Elizabeth finally arrived in New York to begin what became known as the 'G.I. Shuttle', her first such voyage leaving New York for the Clyde on 5th June 1942.

A week after her arrival at Gourock, the QUEEN ELIZABETH sailed for Suez on 17th June (via Freetown and Simonstown) with reinforcements for the British Eighth Army to help stem Rommel's advance towards the Canal. She was back in New York on 19th August to begin her regular G.I. Shuttle work in earnest.

"The voyage, while short, will be extremely difficult for all" With just enough room for a man to squeeze into his standee, with the man above him practically resting on top of him.

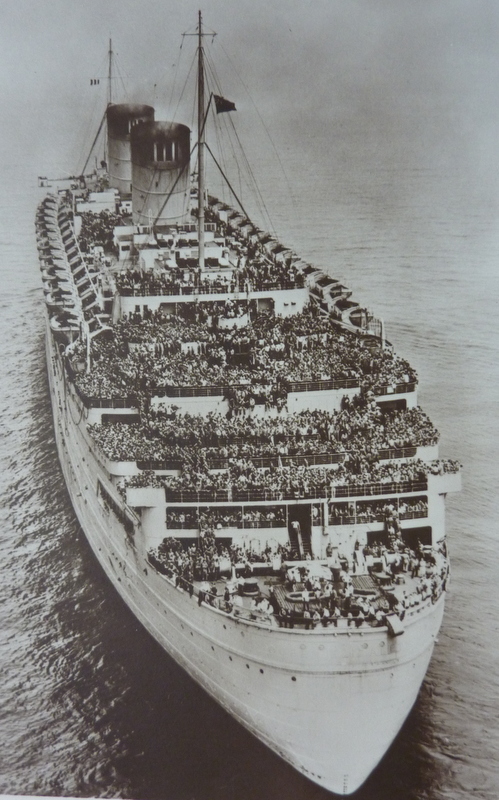

The QUEEN ELIZABETH was now equipped to carry 15,000 troops although the numbers were reduced to 12,000 in the winter months. The troops would board the Elizabeth at Pier 90 at New York during the late evening hours under cover of darkness after being transported to the pier by either ferry or bus. On boarding, each G.I. was given a coloured disc or card (red, white or blue) and this indicated the section of the ship in which he must remain during the voyage. Another essential rule was that each man, regardless of rank, should wear or carry his lifebelt when outside his cabin at all times.

Boat drill was carried out on departure from New York

The safety of the troops during these solo high-speed dashes across the Atlantic was not considered to be paramount in the minds of those at the top. Some 10,000 men could, perhaps, be carried in safety according to the lifeboat and liferaft capacity of the ship, but it was considered that the extra 5,000 men who were carried in summer and not provided for in the life-saving equipment were worth the risk, based on the Elizabeth's existing records of speed and reliability.

Whilst on the G.I. Shuttle, there were six sittings for each of two meals each day in the QUEEN ELIZABETH's first-class restaurant.

For the two meals a day that were provided there were six sittings, each of forty-five minutes. Breakfast was from 6.30am until 11.am; and dinner from 3.pm to 7.30pm. Sir James Bisset was in command of the QUEEN ELIZABETH for many of these 'shuttle' voyages. Following his retirement, Sir James was in great demand as a lecturer and one day was telling some schoolchildren of the days when 2,000 lbs of bacon and 32,000 eggs were cooked for breakfast every day. When he asked for questions, one boy shot up his arm and asked: "How big were the frying pans?" !!!

In November 1942, the QUEEN ELIZABETH was involved in an incident that still remains the subject of much speculation. The U.704, under the command of Kapitan Horst Kessler, was wallowing in a Force 8 gale off the west coast of Ireland before returning south to its base in France. Early in the afternoon of 9th November a large, two-funnelled steamer was sighted, some six to seven miles away. The submarine dived and the captain identified the ship as the QUEEN ELIZABETH. Four torpedoes were fired and the U-Boat followed their course. One detonation was heard. Apparently the torpedo had exploded well away from the ship. Captain Bisset said, after the war, that an explosion was heard, "and we increased to 31 knots without any trouble."

The steamer observed by Kessler had been travelling at speed. She then stopped for a few minutes before proceeding on her way. Kessler always maintained that the ship was the QUEEN ELIZABETH. All the Cunard records from that period have apparently been lost.

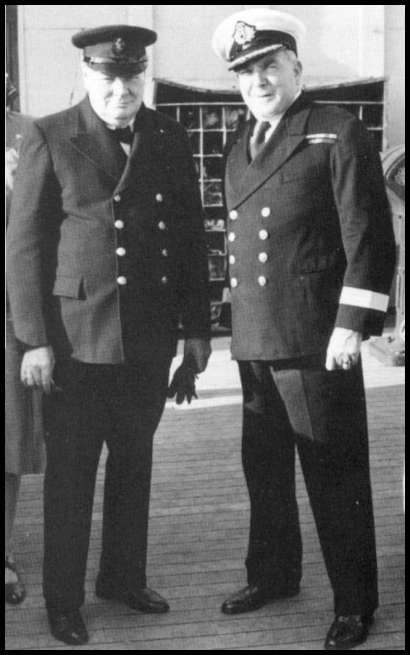

Commodore James Bisset with Winston Churchill on the QUEEN ELIZABETH

However, to stop the QUEEN ELIZABETH would take considerable time. The superheated steam needed to be cooled to normal working temperature before slowing the ship could even be considered. This would take at least an hour plus many miles, and this would not have allowed her to stop within Kessler's observation.

Altogether the QUEEN ELIZABETH made 35 round voyages across the North Atlantic on the 'G.I. Shuttle'. During this time, and for a while after, she was under American control through a lend-lease agreement. She did, however, remain all the while under Cunard management with British officers and crew. Throughout the 'G.I. Shuttle' the two Queens were never in the same port at the same time, and the schedules avoided either ship lying at anchor at Gourock during the period of full moon.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH at anchor at the Tail of the Bank off Gourock in the Firth of Clyde, the U.K. terminal port for the G.I. Shuttle.

Of all the arguments used in the United States to support the demand for subsidies for American merchant shipping, none has been advanced with greater potency than that America had to rely on foreign ships in the Second World War, and could not afford to do so again. This argument was buttressed by the statement that the British Government charged the United States for transporting American troops in the QUEEN MARY and the QUEEN ELIZABETH. Sums amounting to $100 million were freely bandied about in the coumns of newspapers as the cost of carrying G.I.s to and from the theatres of war. Denials of this speculation by British shipping representatives were not accepted. It can be appreciated that the jibe that Great Britain charged $100 a head to take soldiers to the battlefields of Europe was calculated to be extremely hurtful to Anglo-American friendship.

In an lighter vein, it should not be forgotten that it was a G.I. being transported (not for $100) in the QUEEN ELIZABETH who, in a burst of enthusiasm, said to one of the officers: "Say, why can't you British build a ship like this?" !!!

The QUEEN ELIZABETH approaching her wartime anchorage at the Tail of the Bank.

Between April 1941 and March 1945 the QUEEN ELIZABETH steamed 492,635 miles and carried 811,324 'passengers'. The highest number that she carried on any one voyage was 15,932 passengers and crew, but the record for the highest number ever carried in one ship goes to the QUEEN MARY with 16,683.

After V.E. Day it fell to the Queens to transport back to the United States many of the hundreds of thousands of the G.I.s they had brought to Europe, and, in the case of the QUEEN MARY, to transport 25,000 American servicemen's 'War Brides' and their children to their new home country. And so, on 24th June 1945, the QUEEN ELIZABETH left Gourock with her first load of returning G.I.s. Their welcome in New York was, to say the least, tumultous. The QUEEN ELIZABETH left Gourock for the last time as a troopship on 7th August 1945, flying flags which spelled out: 'Many thanks. Gourock farewell'.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH's after decks packed with U.S. troops on a G.I. Shuttle crossing.

A fortnight later, on Monday 20th August 1945, the QUEEN ELIZABETH arrived in Southampton for the first time - four and a half years late. During the turnround in New York on her second G.I. Shuttle voyage from Southampton, Commodore James Bisset had the Elizabeth's wartime grey funnels repainted in Cunard's red and black. The result brightened up the ship considerably after the years of drabness. From 22nd October 1945 it was the QUEEN ELIZABETH's job to repatriate thousands of Canadian soldiers. Four days later she arrived at Halifax, Nova Scotia, with 12,517 passengers and 864 crew. However, Commodore Bisset was not happy with the location of the quay alongside which the Elizabeth was berthed and considered it too exposed should a strong south-east wind blow up; the resulting swell would cause the ship to range back and forth, possibly breaking her moorings. In spite of the understandable Canadian protestations that they wanted their soldiers to step directly on to Canadian soil, Commodore Bisset recommended that future repatriations should be to either New York or Boston.

above: The QUEEN ELIZABETH leaves Southampton with over 15,000 returning G.I.s in August 1945, and below: her triumphant arrival at New York

On 6th March 1946, when the QUEEN ELIZABETH arrived back in Southampton, the Ministry of War Transport announced that the ship would be the first ocean-going passenger steamer to be released from His Majesty's Government service. To a post-war Britain she was to become what the 'Mary' had represented to the country after the Great Depression - a national symbol of recovery from adversity. For the QUEEN ELIZABETH the war was over. Sir Percy Bates said that he liked to think that the Queens had, by their troop carrying capacities, shortened the war by a whole year. So much for the cynics who, in the early days of the war, had prophesied that the Queens would lie uselessly alongside their safe pier in New York for the duration of the war!

It was agreed that the QUEEN ELIZABETH should spend twelve weeks on the Clyde (at her old wartime anchorage) plus ten weeks at Berth 101 in Southampton and in the King George V dry dock. Half her crew was paid off and went on leave, whilst around 400 remained with the ship for maintenance, fire watch and to sail the ship on the coastwise voyage to the Clyde.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH left Southampton on 30th March 1946 and arrived and anchored off Greenock the following day. It was out of the question for the Elizabeth to sail up to John Brown's shipyard at Clydebank, so it was planned to ferry men and equipment out to the liner as she lay at anchor off the Tail of the Bank. At the end of her time at Gourock one thousand Clydebankers ('Bankies') sailed south with the ship to alleviate the acute shortage of local skilled labour at Southampton.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH at anchor at the Tail of the Bank in the Firth of Clyde as John Brown's workmen transform her from a troopship to passenger liner in April 1946.

Many of the QUEEN ELIZABETH's fittings had been placed ashore in New York, Sydney and Singapore when she was converted into a troopship and all these globally scattered items had to be returned to Southampton for refurbishment, assembly, sorting and fitting. Works of art were also renovated by the original artists.

On 7th August 1946 the QUEEN ELIZABETH entered the King George V dry dock where her 140-ton rudder was inspected. Her propellers were removed and cleaned and the underwater hull cleaned and painted. The anchors were examined and each link of her anchor chains painted. In total the reconversion work cost £1 million.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH entering the King George V Dry Dock at Southampton

The QUEEN ELIZABETH was ready for her trials in early October and sailed for the Clyde on the sixth of the month. The maiden voyage had been arranged to depart from Southampton on 16th October 1946. Sir Percy Bates told Commodore Bisset: "We do not expect you to attempt to make speed records either on the trials or on the maiden voyage. The QUEEN MARY still holds the Blue Riband with her 1938 eastbound crossing at 31.69 knots, and that is quite good enough."

The QUEEN ELIZABETH making almost 30 knots on her sea trials over the Arran Mile on 7th October, 1946

Queen Elizabeth and her daughters Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret joined the QUEEN ELIZABETH for the trials on 7th October. They were ferried out to the liner on the Clyde steamer QUEEN MARY II. At 11.15am the QUEEN ELIZABETH weighed anchor and was abeam the Cumbraes an hour later. At 3.pm the liner commenced her northward run over the Arran measured mile and covered the course in 2 minutes 1.3 seconds which gave an average speed of 29.71 knots. A southbound run produced a speed of 29.75 knots. At 3.50pm the Cumbraes were once again abeam and the QUEEN ELIZABETH anchored at the Tail of the Bank at 5.pm.

Commodore James Bisset gives advice to Queen Elizabeth as she takes the wheel of the QUEEN ELIZABETH

The following day, 8th October, four hundred guests of the Cunard Company boarded the QUEEN ELIZABETH for the return passage to Southampton. The Elizabeth sailed at 8.pm. The following morning a small coastal collier was seen in the Irish Sea wallowing along at 6 knots. The small vessel's skipper hoisted a flag signal: "What ship is that?" As required by law, Commodore Bisset obligingly raised the Cunarder's recognition flags 'G B S S'. The QUEEN ELIZABETH docked at Southampton at 11.am on 10th October.

In all, 2,228 passengers had booked passage on the QUEEN ELIZABETH's maiden voyage. Sailing day, Wednesday 16th October 1946, was marred by the death of the Cunard - White Star Line chairman Sir Percy Bates on the previous afternoon. Promptly at 2.pm the liner pulled away from the quayside. There was no call at Cherbourg; the ship was fully booked from Southampton and much work still needed to be done to make the harbour at the French port safe again.

Promptly at 2.pm on 16th October 1946, the QUEEN ELIZABETH leaves Southampton on her first ever commercial voyage.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH encountered a severe storm on 18th October, the day on which Commodore Bisset had arranged a memorial service for Sir Percy Bates.

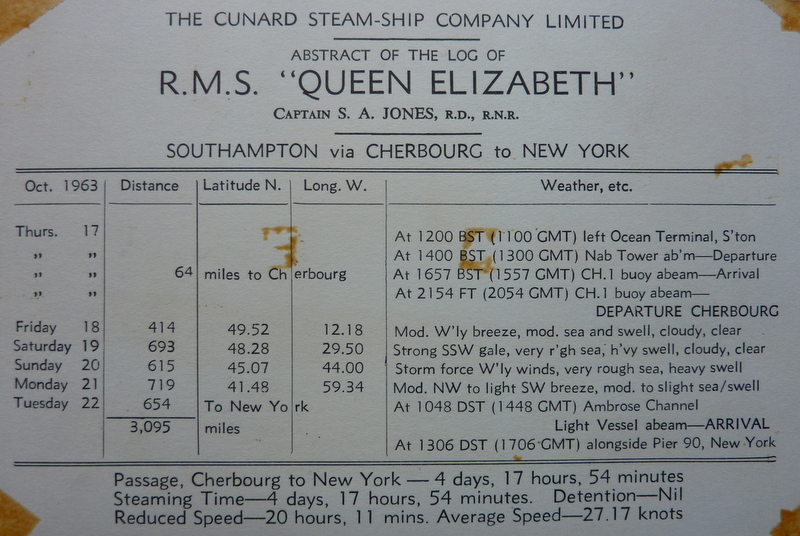

Because of a strike by New York tugboat men there was a possibility that the QUEEN ELIZABETH would be diverted to Halifax. However, because of the prestigious nature of the Elizabeth's maiden arrival at New York as a commercial passenger liner, Commodore Bisset decided to press on and dock the ship at Pier 90 without the aid of tugs if necessary. The QUEEN ELIZABETH passed the Ambrose Channel Light Vessel off New York just before dawn on 21st October after a passage of 4 days, 16 hours and 18 minutes at an average speed of 27.99 knots.

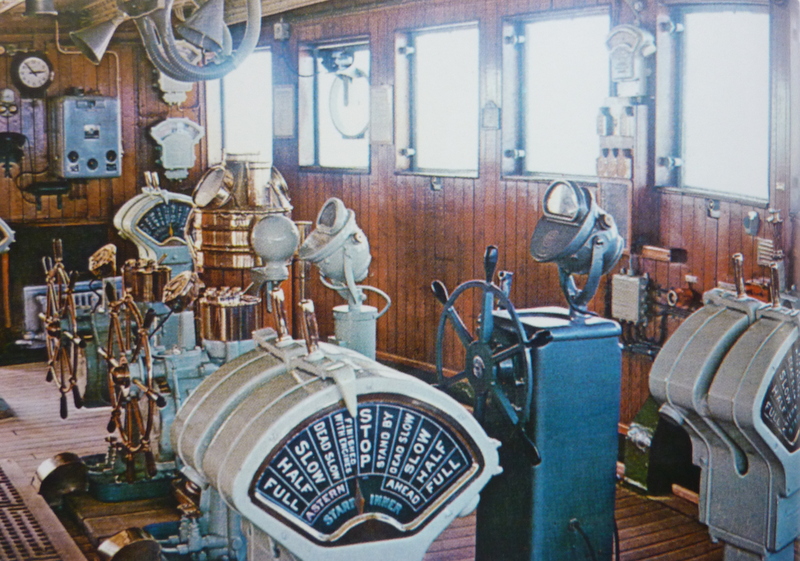

The QUEEN ELIZABETH berthed alongside the Ocean Terminal at Southampton, taking on bunkers for her next voyage

On 14th April 1947 the QUEEN ELIZABETH was homeward bound and after leaving Cherbourg encountered thick fog in the Channel. Cunard's appropriated pilot, Captain Bowyer, was not available as he was 'fogbound' on another vessel. And so rota pilot F.G. Dawson boarded the Elizabeth off the Nab Tower. He had no experience of handling ships as large as the 'Queens' and off Calshot at the entrance to Southampton Water the QUEEN ELIZABETH ran aground. Her master, Captain Ford, had attempted to avert the incident by ordering 'half-astern' on the starboard engines, but it was too late. Her propellers thrashed the shallow water into billowing clouds of yellow and black as sand and mud were churned up from the sea bed. On the bridge there was the faint sensation of a slight, lurching jolt which some on board never even felt. Captain Ford then stopped the engines to avoid sucking silt into the underwater inlets. The QUEEN ELIZABETH was embedded in mud to a point just below the bridge. By coincidence she had grounded in almost the same geographical spot as the AQUITANIA, ten years previously almost to the day.

Staff Purser Brent Jenkins (left)

A signal for assistance was sent and - within the hour - the company, port and salvage officials were on board and in conference with Captain Ford. The tender ROMSEY which had brought the officials out to the stricken ship made a solo attempt at pulling the liner off the mud, but the towline parted under the unequal strain. By six o'clock the next morning, thirteen tugs had arrived from Southampton, Portsmouth Dockyard and Poole. Only a little fuel remained after the transatlantic crossing, but a barge moved alongside to take it off as necessary. The salvage attempt at the first suitable high tide failed and the Elizabeth had to wait until 17th April when at 8.40pm she was finally pulled off the mud. There was still thick fog in Southampton Water and the QUEEN ELIZABETH returned to Cowes Roads to anchor overnight. The following morning, 18th April 1947, she steamed into Southampton - fifty hours late !

Other than silt found in some inlets, there was very little evidence of the grounding. Internally the condensers and oil cooler inlets were cleared of shells and gravel.

The starboard side of the boat deck on the QUEEN ELIZABETH (photo : John Shepherd)

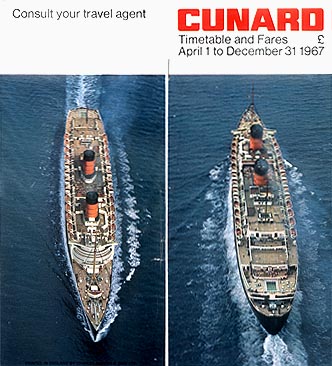

The QUEEN MARY's post-war refit was completed in the summer of 1947 and on 1st August she joined her larger sister in the long-delayed two-ship Atlantic express ferry service for which they had both been built.

Sir Percy Bates' dream of a weekly trans-Atlantic service operated by just two express steamers became a reality in August, 1947.

During almost two decades following the end of the Second World War, young men in Britain were 'called up' for two years of National Service in the armed forces. An alternative was serving in the Merchant Navy, and the prospect of earning £2 a week in the forces, or being well paid in the merchant service proved to be a one-sided choice for many youngsters.

Looking forward from the first-class sports deck on the QUEEN ELIZABETH (photo: John Shepherd)

The QUEEN ELIZABETH never enjoyed the same affection that the Cunard men held for the QUEEN MARY, being described as the 'colder' of the two ships. She was nonetheless a popular ship. The loyalty that she was given by her crew, the lifeblood of any ship, was reflected in the service given to her passengers who patronised the ship in vast numbers time and time again. The popularity of the two 'Queens' meant enormous profits for the Cunard Line and the two ships repaid their original investments many times over. They became an establishment, a familiar sight to those who saw them arriving and departing, and a way of life to the crew who sailed them. All this seemingly had no end, but this complacency would be destroyed completely in the 1960s.

The view ahead on a sunny day in the North Atlantic (photo: John Shepherd)

On 28th July 1948 King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, accompanied by their younger daughter Princess Margaret Rose, were received on board the QUEEN ELIZABETH, the flagship of Britain's merchant fleet. The purpose of the visit was to enable Queen Elizabeth to present the ship with her personal standard, to be framed and hung in the first-class restaurant. But the prime reason for the day's visit was for the Queen to unveil a portrait of herself. Originally vetoing the idea of allowing her portrait to be hung in the ship when the liner was launched, Queen Elizabeth had now relented. Her brother, the Hon. David Bowes-Lyon, had recently been appointed to the Board of Cunard and had arranged for Sir Oswald Birley to paint the portrait which was hung in the first-class main lounge.

Queen Elizabeth and King George VI are received on board the QUEEN ELIZABETH by Captain Ford on 28th July 1948

King George VI, Queen Elizabeth and Captain Ford with senior officers on the starboard bridge wing of the QUEEN ELIZABETH

On 1st January 1950 the Cunard Steamship Company took over its wholly-owned subsidiary, Cunard - White Star. This cumbersome organisation had involved double-accounting and separate staffing. The only signs of White Star which remained were the buff funnels of the BRITANNIC and the GEORGIC.

Looking astern over the cabin-class sports deck (photo: John Shepherd)

The 'Queens' experienced many difficulties when navigating the Solent due to yacht manoeuvres. On August Bank Holiday, 1950, a yacht cruised across the fairway in the track of the QUEEN ELIZABETH. There was no one on deck, but when the yacht was hailed an old lady appeared from below. On being told that she should not leave the yacht's helm unattended, she shouted that she had gone below to boil some milk! The lady then tied her yacht up to a buoy (a forbidden practice carrying a heavy fine), and two days later Southampton Harbour Board received a letter from the lady alleging her yacht had been 'interfered with' by the QUEEN ELIZABETH.

Lady Assistant Pursers were introduced on the Cunard liners after the Second World War. Photographed on the QUEEN ELIZABETH, sometime in the late 1940s, are (left to right): Elizabeth Sayers, Margaret Morton, Phyllis Davies and Mary Marchant.

On another occasion the Elizabeth had to go full astern because a yacht crossed her path, and as a result the liner's stern touched a mud bank. There was a great rumpus and the yacht owner was traced. The offender turned out to be a retired rear-admiral with a D.S.O.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH leaving her berth at Pier 90, New York (photo: John Shepherd)

The scene on the port wing of the QUEEN ELIZABETH's bridge as the ship swings in the Hudson River before heading down river, across New York Bay and out to sea.

On 8th September 1951 the QUEEN ELIZABETH left Southampton on her 100th round voyage to New York since she entered passenger service in October 1946. During the five years she had carried 300,000 passengers.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH alongside the Gare Maritime at Cherbourg

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor were regular passengers on the QUEEN ELIZABETH between New York and Cherbourg

The first hint of competition from the airlines came in October 1951 and this resulted in speeding up the turn-round of the 'Queens' in 1952. Additional competition in the form of the new UNITED STATES would also be a factor from mid 1952. In 1951 the 'Queens' sailed from Southampton every 15 or 17 days, but the 1952 schedules show each liner sailing every fourteen days, enabling fifteen round voyages to be made between May and October compared with just eleven in 1951. This limited the turn-round at both Southampton and New York to just 36 hours which by current standards sounds very leisurely indeed!

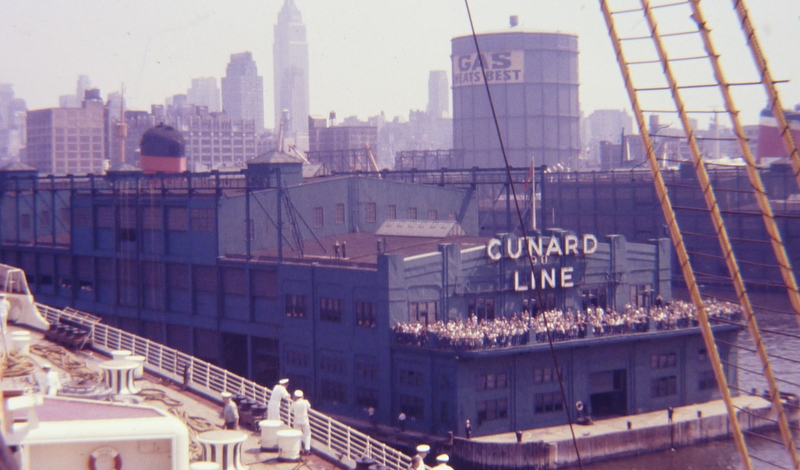

Friends of passengers wave 'farewell' at the end of Pier 90 (photo: John Shepherd)

In June 1952 the QUEEN ELIZABETH was recording some very fast passages, just prior to the entry into service of the UNITED STATES on 4th July. In mid Atlantic on 6th June she steamed 700 miles at an average of 30.43 knots, her fastest day's run since entering passenger service after the war. The crossing from New York to Cherbourg - 3,195 miles - was made in 4 days 13 hours and 6 minutes at an average speed of 29.29 knots. On her next voyage, the week before the maiden voyage of the UNITED STATES, the QUEEN ELIZABETH averaged 31.09 knots for one day's run. This should be seen in the context of the QUEEN MARY's record of 31.69 knots when she took the Blue Riband of the Atlantic in September 1938.

From the mid 1940s until the mid 1950s both the 'Queens' were given a short summer overhaul at Southampton. For instance, the QUEEN ELIZABETH was out of service from 21st July to 30th July 1952 and this included six days in the King George V dry dock. The summer overhauls were routine and no special work was done.

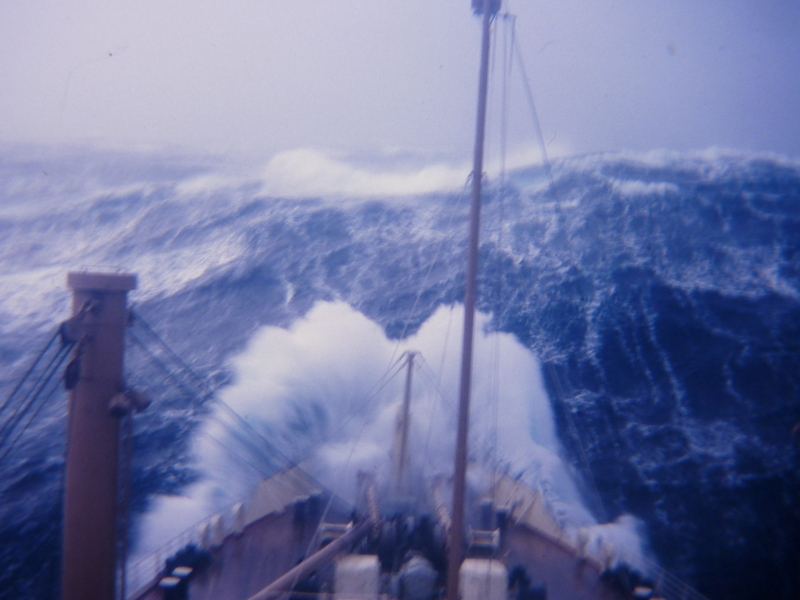

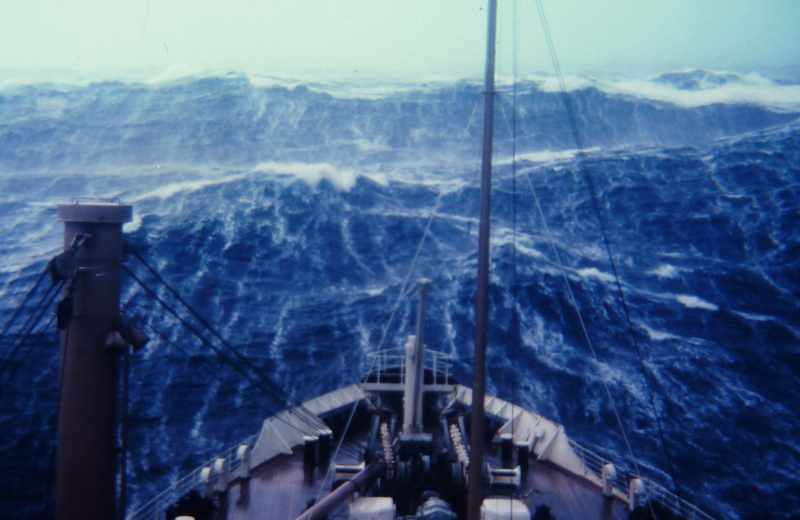

Winter conditions in the North Atlantic (photo: John Shepherd)

The Hales Trophy, awarded for the Atlantic speed record, left Southampton on 8th November 1952 on board the new holder, the UNITED STATES, which crossed from New York to Bishop Rock at 35.59 knots on her maiden voyage. The QUEEN MARY gained the Blue Riband for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic from the NORMANDIE in 1938, but the Cunard Line always refused to accept the trophy. It remained in the NORMANDIE until the outbreak of war, after which it was returned to the Hanley jewellers who made it.

The UNITED STATES took the 'Blue Riband' on her maiden voyage

It is said that ship repairers always complain that shipowners never give them long enough to complete annual overhauls. Be that as it may, John Thorneycroft's staff at Southampton were set a formidable task with the QUEEN ELIZABETH's overhaul in January 1953. In addition to the normal painting, scaling, underwater inspection, removal of propellers, drawing of tailshafts and so forth; 157 tourist-class cabins were given air-conditioning and provision was also made to carry more fuel.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH in the King George V dry dock at Southampton for annual overhaul.

By converting water tanks, an additional 1,000 tons of fuel, or about one day's comsumption, could be carried. Contrary to newspaper reports, this additional oil would not enable the world's largest liner to make the round trip without refuelling, but Cunard would be able to save some money if the current price of fuel oil was cheaper in England than the United States, or vice-versa. The tourist-class cabins on D-Deck were always very warm despite every effort to provide adequate ventilation, and air-conditioning was urgently required. Perhaps the advent of the fully air-conditioned UNITED STATES prompted Cunard to take this measure.

The first-class main lounge on the QUEEN ELIZABETH

During her 1953 overhaul, two fires broke out on board the QUEEN ELIZABETH in dry dock. The first, on 28th January in cabin main-deck 93, was extinguished by Southampton Fire Brigade and the second fire, just twenty-four hours later, was discovered in a C-deck cabin. Both fires were considered suspicious and detectives questioned 2,000 Thorneycroft workmen and some 400 crew. Coincidentally, just one week later, the EMPRESS OF CANADA was burnt out in Gladstone Dock at Liverpool.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH dominates a cricket match during her summer overhaul in the King George V dry dock.

Queen Elizabeth's 'cherished wish' that she might someday sail in the liner was fulfilled in October 1954 when, by now Queen Mother, she embarked at the beginning of a tour to the United States and Canada.

The Verandah Grill on the QUEEN ELIZABETH - exclusively for the use of first-class passengers

In early 1955 the QUEEN ELIZABETH was taken out of service for an extended overhaul from 20th January until the end of March. She was to be fitted with Denny-Brown stabilisers whilst in the King George V dry dock. The installation would be the largest of its kind in a passenger liner and consisted of two sets of stabilising machinery situated in separate compartments. There were four fins, two on either side of the ship. Each fin had an outreach of 12 feet 6 inches and was 7 feet 3 inches wide. The two sets operated independently so that for a moderate roll only one set needed to be used.

On 27th March 1955 the QUEEN ELIZABETH sailed down the Channel as far as the Lizard to test the new stabilisers. The weather was moderate and only slight natural rolling occurred so the liner was force-rolled and the stabilisers immediately became effective.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH in dry dock having her stabilisers installed.

The unreliability of statistics - or should it be said the ability to interpret them in several ways - is illustrated in the case of the UNITED STATES and the QUEEN ELIZABETH. The American liner made 44 Atlantic crossings and carried 70,104 passengers in 1955. This, it is stated, is the largest number carried in any transatlantic ship during the year and gives an average of 1,593 passengers in each sailing. These are undeniable facts. But the QUEEN ELIZABETH made only 38 crossings and yet carried 66,000 passengers, giving a average of 1,752. The fewer crossings were due to the Elizabeth's extended overhaul during which stabilisers were fitted, and if she had made her usual 44 crossings then the results might have been very different.

On a particularly rough crossing in April 1955, during which there were gusts of wind to 70mph and a heavy swell of up to 50 feet, nearly 100 passengers and members of the QUEEN ELIZABETH's crew were hurt. Despite the effectiveness of the new stabilisers to minimise rolling, nothing could be done to reduce the pitching.

Typical winter conditions in the North Atlantic

In January 1957 the Cunard Line announced that it had carried 275,500 passengers across the Atlantic in 1956, an increase of 16,500 over its 1955 carryings. However the year 1957 proved to be the irreversible turning point when an equal number of people were transported by air as were carried by sea.

On 26th October 1958 the first American commercial jet took off for Paris and a whole new era was born. With flight time cut from twelve to less than seven hours, the lure was irresistible. By 1960 the jets had 70% of the transatlantic business.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH alongside the Ocean Terminal at Southampton as the QUEEN MARY passes her, outward bound for New York.

At the Cunard Steamship Company's Annual General Meeting held on 28th May 1959, the Chairman Colonel Denis Bates speculated on how the world would be travelling in the future. The route between America and Europe had characteristics very different from others, said Colonel Bates. It is comparatively short - a long weekend by the express steamers or six and a half hours by air. Some two thirds of Cunard's passengers crossed the Atlantic on holiday: hence the company's slogan 'Getting there is half the fun'. The next largest category comprised business travel and if current medical opinion was correct there was a danger that modern airspeed had outstepped the capacity of man to adapt himself to its stress. Air travel increased across the Atlantic by 26% in 1958, whilst sea carryings reduced by just four and a half per cent. Colonel Bates declared that Cunard philosophy had always been that air and sea travel are complementary rather than competitive on the North Atlantic. There was great complacency in the Cunard boardroom: people would always prefer to cross the ocean by liner, and preferably by Cunard !

The forward Observation Bar on the QUEEN ELIZABETH

Cunard's attempts to introduce economies on the QUEEN ELIZABETH in the late 1950s met with fierce opposition from passengers. Artificial flowers were tried with the result that the company was inundated with complaints and Cunard rapidly re-introduced fresh flowers at a cost (in the late 1950s) of £850 per voyage.

In September 1959 an announcement was made to the effect that an independent committee of three, headed by Lord Chandos, had been set up to examine the Cunard Company's proposals for replacing the 'Queens'.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH had an unexpected stowaway in 1959. A parakeet flew in through an open porthole at New York and quickly became the mascot of the ship's officers who bought him a fancy cage and named him Joey. After several crossings with Joey on board, the crew began to grumble that the weather seemed to have taken a turn for the worse. They blamed it all on Joey and reports finally got back to the Commodore who ruled that Joey must go !

The year 1960 proved to be another good one for Cunard. The Company's liners carried 207,563 passengers or 23.95% of the combined total of passengers carried by all transatlantic shipping lines in 1960. The continuing popularity of the 'Queens' was shown by the fact that they carried 110,800 passengers between them in 1960. In 1961 Cunard liners were to make 207 sailings to and from New York.

The general assumption that the replacements for the 'Queens' would be built at Clydebank touched a nerve with Dr Dennis Rebbeck, deputy managing director of Harland & Wolff, Belfast. He said that it had become a source of irritation to him and his colleagues on the board. "Public memory is notoriously short," said Dr Rebbeck, "It has apparently been forgotten that in 1927 we laid the keel of a 1,000 foot passenger liner for the White Star Line. Though it was started it was never finished, due to the economic blizzard in the late 1920s."

The promenade deck main square on the QUEEN ELIZABETH

In late 1961 Cunard installed fruit machines (popularly known as one-armed bandits) on the QUEEN ELIZABETH and was immediately criticised for resorting to such a revenue-producing device on a luxury liner of this class. The experiment lasted three voyages before the bandits were given a dishonourable discharge.

The 'Cassandra' column in the 'Daily Mirror' on 29th November 1961 was uncharacteristically enthusiastic about the QUEEN ELIZABETH. It read: "She is the last agency of truly comfortable and agreeable travel the world will ever know, since she will never be replaced on any comparable scale of sumptuousness."

The Cunard Line carried 177,547 passengers across the North Atlantic in 1961, 30,000 below the previous year's total. During the year there were 24 fewer westbound sailings and 22 fewer eastbound sailings than in 1960. The passenger carrying business was now losing money: £1.9 million in 1962, £1.6 million in 1963 and £3 million in 1965. However the QUEEN ELIZABETH still carried a full complement on occasions: over 2,000 passengers were on board on one eastbound sailing in June, 1963.

The first-class restaurant on the QUEEN ELIZABETH

The summer overhauls for the 'Queens' were abandoned in 1962 which meant that the two liners would both be available at the height of the tourist season, instead of being 'off duty' for a week to ten days. The QUEEN ELIZABETH was reported as being in excellent shape with her engines in tip-top condition. Cunard faced formidable competiion in the shape of the brand new liner FRANCE and the UNITED STATES operating a weekly integrated transatlantic service.

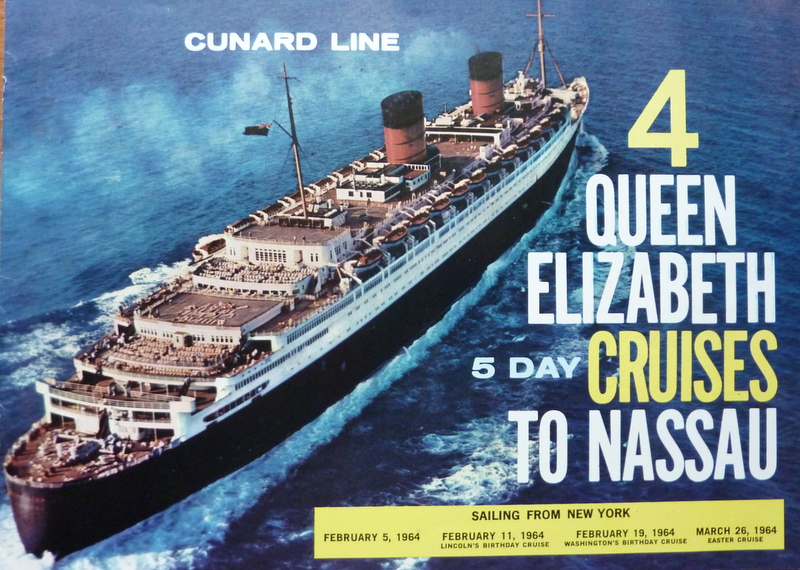

In May 1962 the Cunard Line announced that, for the first time ever, the QUEEN ELIZABETH would be going cruising. Three five-day cruises between New York and Nassau, Bahamas were planned for February and early March 1963, after which the liner would return to Atlantic service. The minimum rate for each cruise would be $185 or £66. The passage time to Nassau would be 39 hours each way, giving passengers almost two full days there. Although the QUEEN ELIZABETH could carry 2,200 passengers, the number would be limited to about 1,200 whilst cruising.

In July 1962 Sir John Brocklebank, the chairman of the Cunard Steamship Company, said that the QUEEN ELIZABETH still had many years to go and mechanically could be kept competitive for the foreseeable future. The Cunard Board had decided, therefore, in view of the changing pattern of the passenger business, much of which could be attributed to political anxiety, that it would be foolish at this juncture to embark on a new capital ship. Sir John went on to say that he believed 1962 would show an improvement over 1961, but it was impossible to say how much at that stage.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH at anchor off Nassau, Bahamas

Three years later it was announced that the QUEEN ELIZABETH would return to the Clyde in December 1965 for extensive improvements by her builders, John Brown & Company. The work would include the installation of full air conditioning, the fitting of private showers and toilets in much of the cabin class and tourist class accommodation, and the creation of a lido at the after end of the promenade deck, incorporating an outdoor heated swimming pool. The QUEEN ELIZABETH arrived back in the Clyde on 4th December 1965 and entered the Firth of Clyde dry dock at Greenock on 9th December. She remained there until 11th March 1966 undergoing the £1.75 million refit and returned to Southampton with about 400 workmen on board who were completing the modernisation of cabins. The QUEEN ELIZABETH was back in service on the North Atlantic on 26th March 1966, but with 150 cabins still not completed, she carried Harland & Wolff workmen with her to finish the job.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH in the Firth of Clyde (Inchgreen) dry dock at Greenock in February 1966

The QUEEN ELIZABETH passing the Cloch Lighthouse on her departure from the Clyde on 12th March 1966.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH departing from the river of her birth, and her wartime home port, for the very last time on 12th March 1966.

It was not only the declining fortunes of Cunard's passenger business which threatened the fleet of which the QUEEN ELIZABETH was still the flagship. Labour disputes at sea and ashore also menaced the liner's schedule and on such occasions she was used as a massive pawn in various disputes involving tugmen, dockers, longshoremen or the crew. In November 1948 a series of strikes dragged on for sixteen days, and on 2nd December the QUEEN ELIZABETH had sailed on the same tide as the QUEEN MARY and the AQUITANIA, a unique event in the history of all three vessels.

A group of the Purser's staff in the Tourist Purser's cabin on the QUEEN ELIZABETH in October 1963.

Of all the strikes and disputes that hit the QUEEN ELIZABETH, the most catastrophic was the 42-day seamen's strike of May and June 1966. This was the catalyst, but not the only cause, of the withdrawal of the two 'Queens'. On 16th May 1966, just six weeks after completing her overhaul on the Clyde, the QUEEN ELIZABETH became the first major casualty of the strike and was laid up at Southampton. The 1966 strike cost Cunard an estimated £3.75 million in lost revenue and brought the total operating loss for the year to over £6 million. Sir Basil Smallpiece (Cunard's chairman since November 1965 when he succeeded Sir John Brocklebank) decided that the time had finally come for drastic, long-delayed surgery on the Cunard passenger fleet. Not only that, but the company headquarters was transferred from Liverpool to Southampton.

The QUEEN ELIZABETH was not successful as a cruise ship. Winter cruises from New York to the West Indies were poorly patronised and one was cancelled and replaced with an unscheduled Atlantic crossing. This also suffered from low bookings and became known as the 'Ghost Ship Voyage'. A thirty-seven day cruise from New York to the Mediterranean sailed on 21st February 1967 and was plagued by bad weather and many ports had to be omitted from the itinerary.

The starboard side of the promenade deck, looking aft.

On 8th May 1967, the axe finally fell and it was announced that the QUEEN ELIZABETH would be withdrawn a year earlier than originally planned - in the Autumn of 1968 after a final summer on the Western Ocean. Sir Basil Smallpiece said: "Although the QUEEN MARY's retirement at the end of 1967 had long been forecast, it had been hoped that the results of the QUEEN ELIZABETH's cruise programme last winter would confirm the viability of the Company's plan to keep her in service when the 'Q.4' [launched as the QUEEN ELIZABETH 2] comes along in 1969. In the event the results have been very far from satisfactory, The Board's decision to withdraw the QUEEN ELIZABETH is part of the unrelenting process of facing realities in its determination to put the Company on to a paying basis."

Like a Greek tragedy the tale of woe gathered force. Recently introduced legislation by the International Maritime Commission also influenced the board's decision. The Americans demanded that the QUEEN ELIZABETH be brought up to the new standards of fire protection which would have to include the fitting of additional fire sprinklers and the boxing-in of stairways that could otherwise act as deadly draught tunnels in the event of fire. The work, Cunard estimated, would cost £750,000. However, U.S. legislators had another surprise up their sleeve. When Cunard requested that the Americans send over an inspector to approve the improvement work as it progressed, the authorities declined. The Americans wanted the work to be completed and then for the 'Elizabeth' to sail over to New York for inspection prior to approval and certification. This would mean an expensive 'light' voyage to New York and, if the inspection failed, an equally expensive 'light' return trip back to the U.K. The prospect to Cunard was just too daunting, and contributed greatly to the decision to dispose of the QUEEN ELIZABETH.

As soon as the decision to retire the 'Elizabeth' was made public, her cruises and Western Ocean crossings became popular with those who had travelled on and had loved the ship over the kength of her career. For the first time in several years the QUEEN ELIZABETH began to show a profit.

The QUEEN MARY and the QUEEN ELIZABETH met for the last time when they were both at sea. Just after midnight on 25th September 1967 the two 'Queens' passed each other in mid-Atlantic, the QUEEN MARY making her final eastbound transatlantic crossing. Within a few short minutes the plans, hopes and successes of three decades came to an end as syrens boomed out across the water, the whole poignant scene witnessed by just a few passengers braving the night wind.

The QUEEN MARY found a buyer in the form of the City of Long Beach, California and she left Southampton on 31st October 1967 carrying 1,000 passengers on what was billed as 'The Last Great Cruise', involving a passage around Cape Horn. The whole affair turned into a spectacular fiasco as the 'Mary' was undercrewed and had to cross the equator twice without the benefit of air-conditioning. To economise on fuel, the QUEEN MARY was using just two of her four propellers. Cunard had warned the new buyers against carrying passengers and would have nothing to do with the bookings, but nevertheless carried the blame in the eyes of the disgruntled passengers.

The wheelhouse on the QUEEN ELIZABETH

Scrapping seemed to provide the obvious, almost humane, answer to dealing with the problem of the QUEEN ELIZABETH. However, over the winter of 1967/68, Cunard received several serious enquiries from potential buyers. The Japanese wanted her for a marine science museum in time for the 1970 Tokyo World Fair. Honolulu was interested as were the Australians. Evangelist Billy Graham offered £2.1 million for her to become a floating bible school, and the United States Institute of Technology wanted her to become a floating university. On 5th April 1968 Cunard announced its decision. For $7.75 the QUEEN ELIZABETH was sold to a group of Philadelphia businessmen.