LIVERPOOL SHIPS

THE BOOTH LINE'S 'HILARY' OF 1931

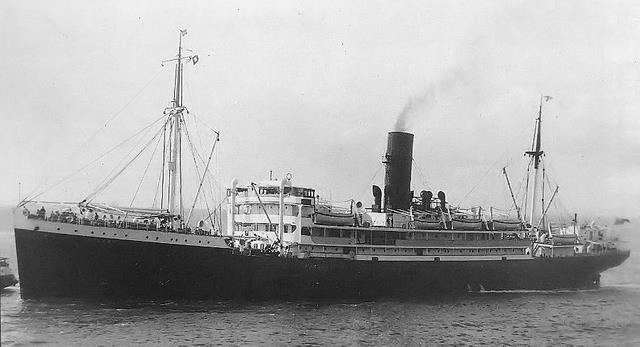

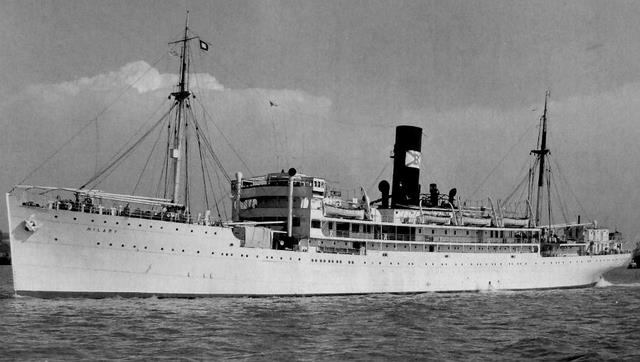

The Booth Steamship Company's HILARY of 1931 operated the Booth Line service from Liverpool to Manaus, 1,000 miles up the Amazon

Built by Cammell Laird & Co. Ltd. at Birkenhead in 1931 Official Number: 162350 Signal Letters: G Q V M Gross Tonnage: 7,420 Nett: 4,286 Length: 424.2 feet Breadth: 56.2 feet Owned by the Booth Steamship Company Limited; registered at Liverpoool Single screw steamer, triple-expansion engine, speed 14 knots

The HILARY in her original form with a black hull and a funnel without the Booth Line houseflag.

Ordering the passenger-cargo liner HILARY at the height of the depression was a mark of considerable faith by the Booth Line, and the placing of the order locally on Merseyside was much appreciated.

The HILARY was launched on 17th April 1931 and was completed by August of that year. She sailed on her maiden voyage from Liverpool to Para and Manaus on 14th August. The new HILARY could easily be recognised by her distinctive three-note triple-chime steam whistle.

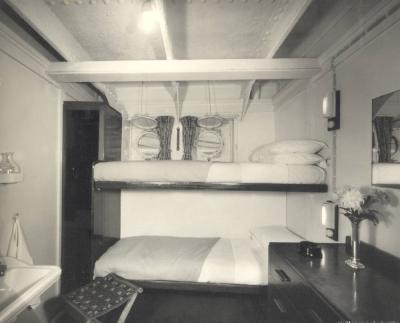

First-class single-berth rooms were on the promenade deck; double and three-berth cabins on the upper deck, and there were four de-luxe staterooms with private bath and toilet. The third-class passengers were accommodated in two and four-berth cabins on the main deck, in compliance with Portuguese emigrant ship requirements.

The first-class dining saloon on the HILARY

A first-class stateroom on the HILARY

The first-class smokeroom on the HILARY

The tourist-class dining saloon on the HILARY

A two-berth tourist-class cabin on the HILARY

The crew and stewards were quartered forward on the main and upper decks, while the captain and officers were in a house at the fore end of the boat deck.

A sister ship to the HILARY was built in 1935 - the ANSELM - slightly smaller and with a cruiser stern. However, she was lost on 5th July 1941 when she was torpedoed by U-96, some 300 miles off the Azores.

The HILARY's predecessor on the Liverpool - Manaus service was the HILDEBRAND

The HILARY was aground twice in the Amazon during her early years. The first occasion was in November 1935, some 170 miles below Manaus, and in April 1936 she grounded two miles east of Goiabel on the notorious Mandahy Bank. One is reminded of the story attributed to Mark Twain, who, when asked by a passenger if he was the man who knew where the sandbanks were, replied, "No, I'm the man who knows where the sandbanks ain't !"

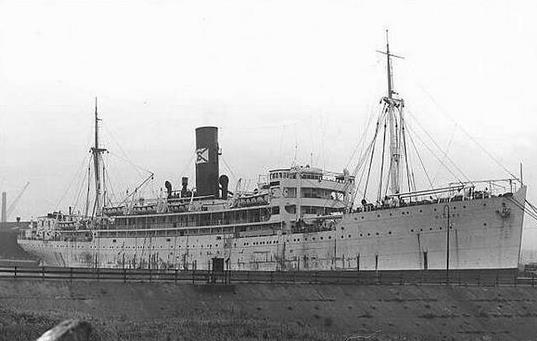

The HILARY docking at the Brunswick Lock, Liverpool

Far more serious was the occasion when the HILARY ran aground on rocks near Holyhead, Anglesey, in dense fog at 12.45am on Easter Sunday 9th April 1939. Because of the fog it was several hours before assistance arrived, but her 100 passengers were eventually taken off safely. The HILARY had sprung a leak forward, but was refloated and towed to Liverpool. It was an unfortunate experience for her master, Captain Lewis Evans of Pwllheli, who was due to retire at the end of the voyage.

On the outbreak of the Second World War, the HILARY was initially left to her owners' commercial service, but in January 1941 she was sent to South Shields and there converted for use as an armed boarding steamer. In May 1941 she sighted two Italian oil tankers off the Azores. One of these was scuttled before the HILARY had a chance to put a boarding party on board, but the other, the GIANNA M, was taken safely to Belfast by a prize crew from the HILARY.

In April 1942 the HILARY ceased to operate as an armed boarding steamer and was returned to Booth Line management, but under Ministry of War orders. On 16th October 1942 she was acting as commodore ship of a convoy bound for New York when her engine room was struck by a torpedo. Luckily for the HILARY, the topedo failed to explode. The story is best told by her then master, Captain A. Elliott:

"We had been followed by enemy submarines for about twenty-four hours, but had not been attacked. However, on the morning of 16th October, at about 10.30am, we heard an explosion and felt a rather heavy tremor in the ship, just as if some other ship in the vicinity had been torpedoed. "The commodore gave an anxious look round his convoy but everything seemed very quiet and peaceful, with all the ships plodding along in their rightful stations. It suddenly struck me that we ourselves might have been hit, although our engines were still turning to the revolutions required. I thought I should send officers to check, and I myself went down to the after end of the ship, but no damage could be seen. "As I came forward again the chief engineer met me and took me down to the dynamo platform where he showed me a large dent in the ship's plates. Some rivets had been sheared off, but there was no leak. "We had been hit by a torpedo in a very vulnerable part of the ship, but although the pistol had gone off, the main charge of the torpedo had failed to explode. If the mechanism had functioned there would have been very little chance of the ship surviving."

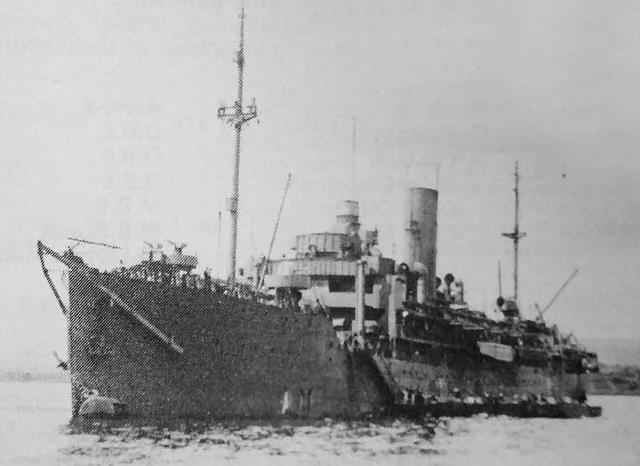

The HILARY as she appeared during the Second World War

In March 1943 the HILARY was again requisitioned, this time as an infantry landing ship. The conversion was carried out by Cammell Laird at Birkenhead. Her passenger accommodation became mess decks, her public rooms communication and control centres, and six landing craft replaced her lifeboats. Armament included at 6-inch gun on the forecastle and a number of Oerlikons; a radar tower was built on the bridge and a searchlight platform constructed between the bridge and the funnel. The HILARY's funnel, masts and superstructure were all left intact and not cut down or removed as with so many converted merchant ships.

With her hull and superstructure painted grey, the HILARY sailed for the Mediterranean where she was based at Algiers, and on 10th July 1943 she took part in Operation 'Husky', the invasion of Sicily, acting as headquarters ship for Admiral Sir Philip Vian. Two months later the HILARY was present at the Salerno landing, and in December 1943 she returned to Portsmouth, ready for the invasion of Europe.

In June 1944 the HILARY took part in the Normandy landings as flagship of Force 'J' under Commodore G.N. Oliver. On 23rd June, Admiral Vian transferred his flag to the HILARY after his cruiser HMS SCYLLA had been damaged by a mine.

The HILARY returned to the Mersey in January 1945 and was handed back to her owners. Cammell Laird refitted her for her old commercial trade and provided accommodation for 93 first-class and 138 tourist-class passengers. By the end of 1945 the HILARY was once again sailing 1,000 miles up the Amazon for the Booth Line. She retained her pre-war appearance, but in 1947 the Booth Line houseflag was painted on each side of her funnel. In 1949 the HILARY was converted from a coal burner to an oil burner, and in 1951 she was joined on the Amazon by her new running-mate, the HILDEBRAND.

The HILARY after the war, with the Booth Line houseflag painted on her funnel

When she was twenty-five years old, the HILARY was sent to Antwerp for a four-month major refit, and re-appeared with an all-white hull, the only Booth liner ever to be so treated. She resumed service in April 1956 with her regular route now including calls at Barbados and Trinidad. Later in 1956 the HILARY was chartered to Elder Dempster for three round voyages to West Africa.

On the HILARY's arrival back in Toxteth Dock, Liverpool, on 14th December 1956, Special Branch detectives boarded the ship to investigate the jamming of her steering gear in the Atlantic a week previously. The HILARY had been on her way home from West Africa via Las Palmas with 170 passengers. Third Officer James Turley was on the bridge and had given orders to turn to port when he saw another veseel approaching, but the HILARY would not answer her helm.

The HILARY looking magnificent with her white hull in 1956

The master, Captain T.E. Williams, was summoned, and 'not under command' lights hoisted. An investigation revealed that an eighteen-inch wheel key, used to control heat in the galley, was missing from its usual place, and it was later found jammed in the steering mechanism. It was quickly removed. The wheel key, a heavy instrument three quarters of an inch in diameter, with two lugs at one end for fitting in the locks of steam pressure doors, had been taken from the galley.

For twenty minutes the HILARY was drifting in a busy sea lane. Captain Williams reported that other incidents had taken place during the voyge. Some electrical cable had been found cut or disconnected. The loudspeaker system had failed and the spare parts could not be found, and an alarm instrument on the turbine gear was found smashed.

After two hours of investigation, Inspector Albert Allen of the Home Office Forensic Science Department ruled out the sabotage theory and said that no further police action was necessary. Captain Williams commented: "There must have been a lunatic on board."

The loss of the HILDEBRAND by stranding in fog off Lisbon on 25th September 1957 gave the HILARY a reprieve from the breakers' yard until 1959, when she was sold for scrap. On 12th September of that year she left the Mersey for the last time, under her own steam, bound for the Firth of Forth, where she was broken up by Thos. W. Ward at Inverkeithing.

The HILARY in Bidston Dock, Birkenhead, after her final voyage.

__________________________________________________________

1,000 MILES UP THE AMAZON ON THE 'HILARY'

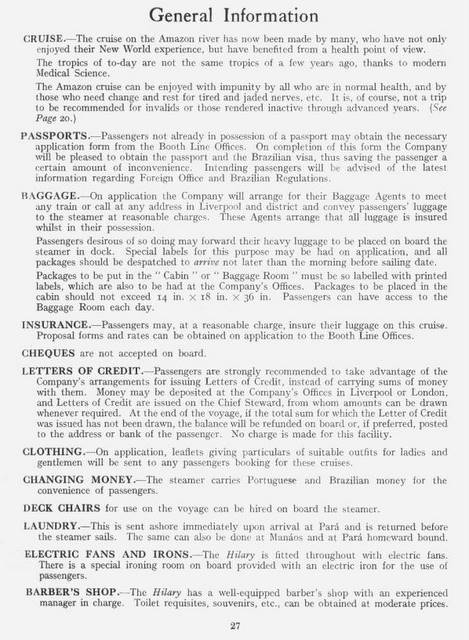

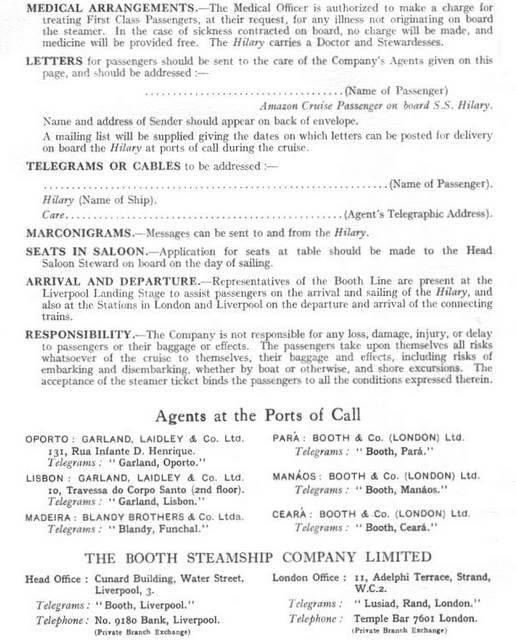

Extracts from the Booth Line brochure for 1932

If a tramcar started from London or Liverpool and made a circle of 11,800 miles at a charge of two pence per mile, the travelling public would be amazed at both the achievement and the price. Yet this is exactly what has been accomplished; only a magnificent liner takes the place of the tramcar, and the charge of two pence per mile includes not only transport, but the services and cuisine of a first-class hotel.

The HILARY leaving Liverpool on a voyage which would take her 1,000 miles up the Amazon

A cruise on an ocean liner is not only a new innovation, but when 2,000 of these miles are accomplished in a luxuriously fitted 7,000-ton vessel on the great Amazon River - the river of mystery - and the heart of the South American continent is penetrated through the equatorial forests of Brazil without a change of cabin from the time of leaving Liverpool to the day of the return to the Mersey, then it becomes not only unique as a cruise, but also a historic achievement in maritime transport and luxurious travel.

Days are spent in quaint cities. Curious natives in the palm thatch dwellings of their jungle homes are passed at many points. Hours speed by swiftly in gliding on tropical rivers through forests of vivid colours alive with bright plumed birds and gorgeous butterflies.

However, before this wonderland of Amazonia is entered, there are scenes of beauty and enjoyment under the blue skies of Portugal, amid the romantic mountains of Madeira and on tropical seas where gales are almost unknown and the broad sunlit ocean is ruffled only by the fresh trade wind and the shoals of flying fish.

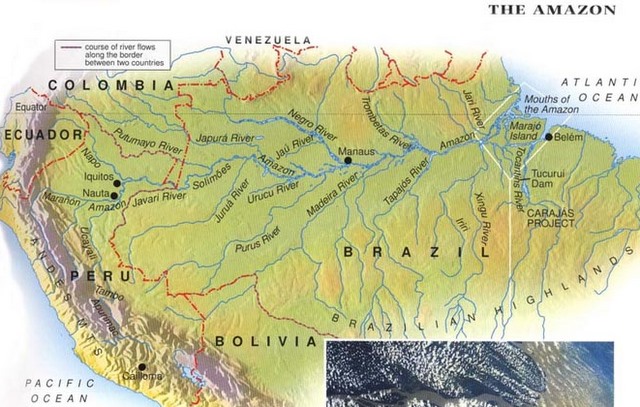

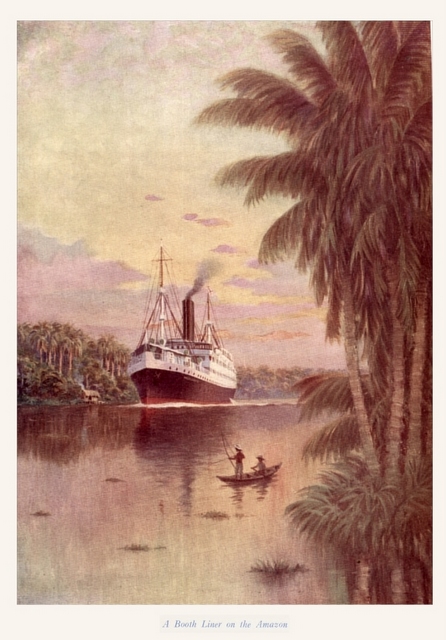

The Amazon

These distant lands, seas and rivers of beauty, warmth and mystery can be reached and enjoyed on the comfortably seated braod decks, or in the palatial staterooms of a 7,000-ton liner, the specially equipped Royal Mail Steamer HILARY.

When the island of Madeira disappears in the deep blue of the sea and the sky, muslin dresses and white drill suits make their first appearance on the decks. Delightful days of rest and pleasure, deck sports and reading, are spent; interspersed with moonlight nights of concerts, dances and lectures. New friendships, new scenes, new thoughts - away from the bustle, hum and smoke of great cities.

Watching the banks of the AMAZON pass by from the deck of the HILARY

From out of the tropical haze has appeared a low shore. It is the first glimpse of the mysterious Amazon which has already changed, with its outflow, the colour of the sea around from deep blue to pale yellow-green.

Soon the HILARY is in the Para River, one of the mouths of the mighty Amazon, here nearly 200 miles broad, but filled with forest-clad islands. Then the great ship, which has brought us across the Equator into the Southern Hemisphere, comes to a momentary rest for official visits from the authorities of the Port of Para - the gateway to the Amazon.

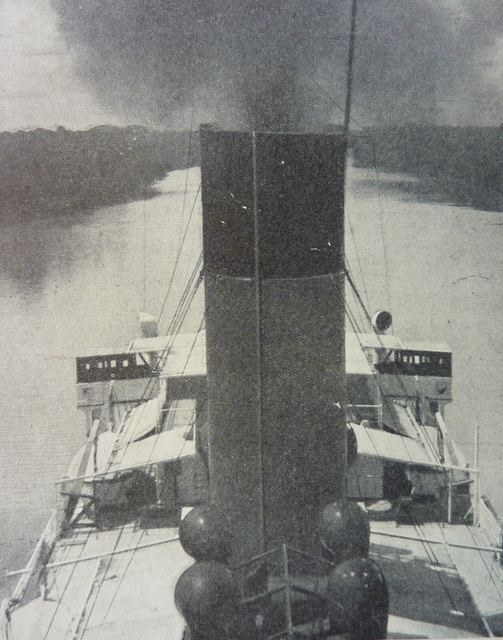

Looking forward from the 'cross-trees' on the HILARY's mainmast as she proceeds up the Amazon.

The HILARY penetrates further into the heartland of Brazil. The immense tropical forest is all around and natives in their dugout canoes cease paddling to gaze in awe at the huge vessel towering above their frail craft.

There is a great mystery in the Amazonian night. Scarcely has the sun disappeared in golden glory behind the interminable walls of the forest, before all around is plunged into darkness. Troops of howling monkeys hold a conversation before retiring, Sometimes the indigo vault is ablaze with the lightning from soundless electric storms.

The town of Obidos is passed during the night. Somewhere in this comparatively narrow section of the river the HILARY passes one of her sister ships coming downstream. The occasion is one for saluting the houseflag.

Some nine miles from Manaus, the HILARY leaves the main stream of the Amazon and enters the Rio Negro. The meeting of the waters of these two giants provides a scene of extraordinary interest. As it name implies, the Rio Negro is comprised of blue-black water, and this forms huge dark patches and miniature whirlpools in the middle of the Amazonian flood. So distinct is the cleavage that the bows of the ship are floating in the dark water, whilst the stern is still supported by the yellow of the Amazon proper.

The confluence of the black waters of the Rio Negro and the muddy brown of the main stream of the Amazon, some nine miles from Manaus.

There seems to be a certain rivalry between Para and Manaus as to which town shall give the more hearty welcome to those who cruise on the HILARY. For whereas Para welcomes the ship with rockets and shots fired in the air, Manaus sends a band on to the quay and residents appear en masse with cheers, spotlessly white clean suits, straw hats and immense bouquets of flowers.

It is easy to write lightly of this hearty welcome. but when one grips the hands of Englishmen in this isolated town, a thousand miles from civilisation - and yet, like an oasis in the desert, possessed of all modern conveniences such as electric light, trams, theatres, cafes and daily newspapers - there is a feeling of pride because English, Scots and Irishmen have had no small share in the achievement.

A section of the Amazon rain forest.

Manaus is a clean town and one is not afraid to eat its food or drink its water. No one could remain long on the ship, or be lonely in hospitable Manaus

One of the HILARY's spacious decks

The leave takings from this remote town are mingled with regret. There is a feeling of sadness as the end of the outward cruise is reached, at a distance of over 5,000 miles from Liverpool, and the HILARY turns her bows downstream.

The same course is followed on the homeward journey and time ashore is usually available at Para, Madeira, Lisbon and Oporto for completing the work of sightseeing. Fancy dress balls on the decorated decks, concerts in the music room and open-air dances lend enchantment to tropical nights.

When the HILARY returns to the broad and busy River Mersey, and this unique cruise is drawing to a close, the traveller will feel that he has been away in fairyland, so many and so unusual have been the sights, sounds and sensations. The Amazon is a river of mystery and provides food for thought and romance long after trips to other lands have faded from memory.

______________________________________________

_________________________________________________

|