LIVERPOOL SHIPS

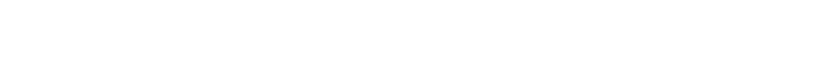

THE CANADIAN PACIFIC LINER 'EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND' (ex 'EMPRESS OF JAPAN')

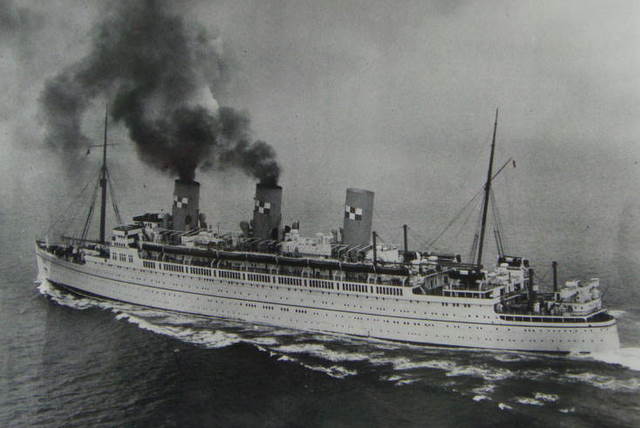

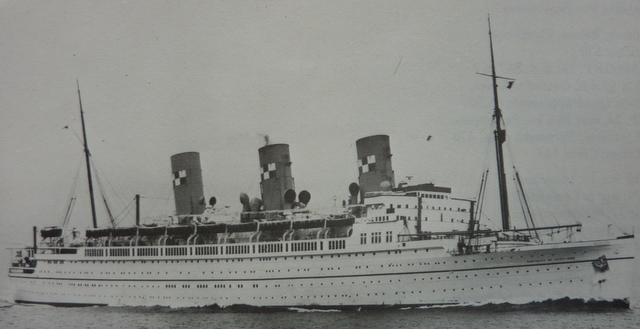

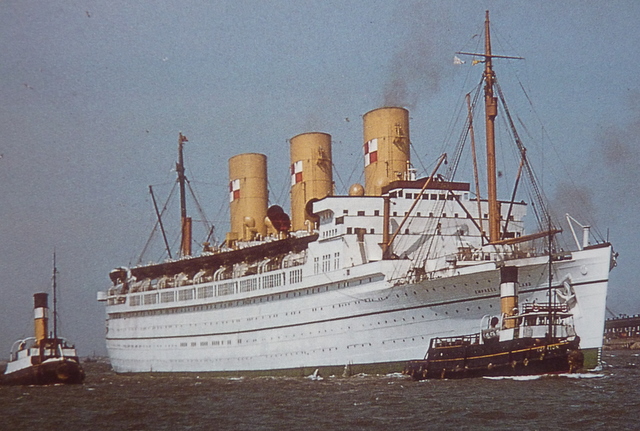

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND looking at her best in her post-war trans-Atlantic colours, and before her masts were shortened. _______________________________________________________ Built by the Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Company, Govan, in 1930 Yard No: 634 Official Number: 161430 Signal Letters: G M L V Gross Tonnage: 26,313 Nett: 14,486 Length: 644 feet Breadth: 83.8 feet Owned by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company (Canadian Pacific Steamships - Managers) 6 steam turbines, single-reduction gearing to twin screws.Speed: 21 knots, max 23. ____________________________________________________________

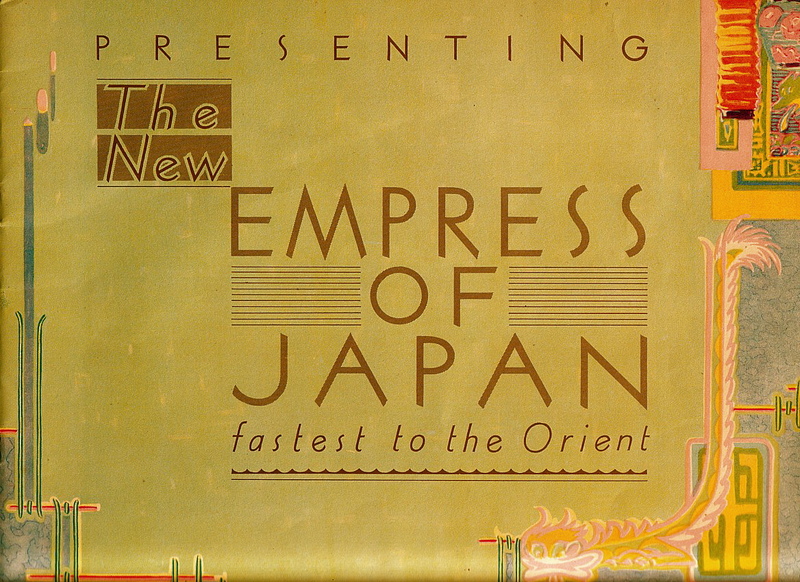

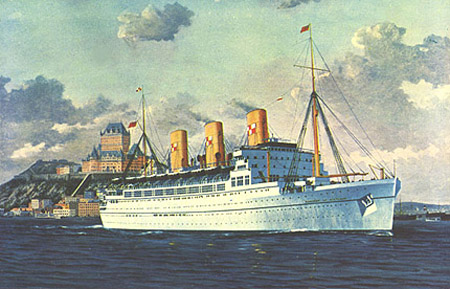

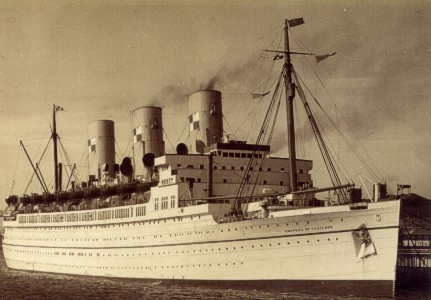

An artist's impression of the EMPRESS OF JAPAN on Canadian Pacfic's trans-Pacific service in the 1930s.

Of all the passenger liners that have ever operated across the North Pacific, the EMPRESS OF JAPAN of 1930, the second vessel to carry this name in the Canadian Pacific fleet, was undoubtedly the finest, largest and fastest.

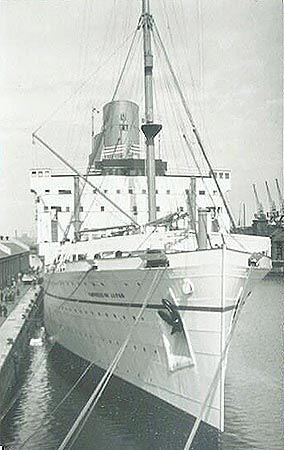

The newly completed EMPRESS OF JAPAN

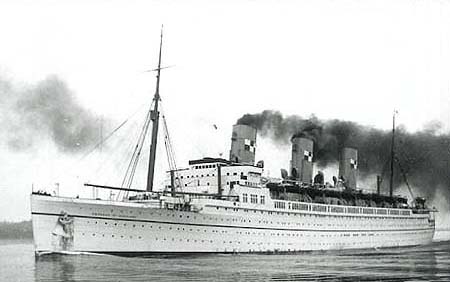

The EMPRESS OF JAPAN was built at the Fairfield Yard at Govan at a cost of about £1.5 million. The ship's twin screws were driven by Parsons' single-reduction geared turbines. Six Yarrow oil-fired water tube boilers supplied steam at 425 lb/psi and 725 degrees superheat. The main engines developed 30,000 shp on five boilers (leaving one in reserve) for a normal service speed of 21 knots. The third funnel was a dummy, but served as a ventilator for the engine room, and the first and second-class galleys.

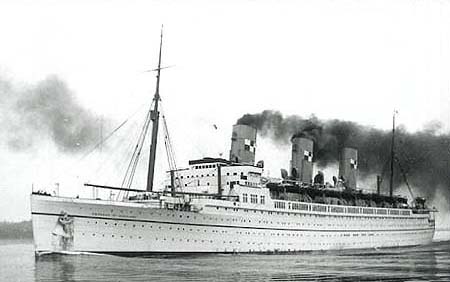

The EMPRESS OF JAPAN in the fitting-out basin at the Fairfield Yard

When the EMPRESS OF JAPAN entered service she could carry 268 first-class passengers; 131 interchangeable; 164 second class; 100 third class and 510 steerage. For cargo she had space for 212,000 cubic feet of general; 33,000 cubic feet for insulated, and 59,000 cubic feet in her silk rooms.

The EMPRESS OF JAPAN having her foremast stepped, February 1930.

The EMPRESS OF JAPAN was launched on 17th December 1929 and was completed in June 1930. She ran her trials in the Firth of Clyde and achieved a maximum speed of 23 knots over the Skelmorlie Measured Mile. On 8th June she was delivered to Canadian Pacific, a truly magnificent ship, beautifully proportioned, graceful, and yet with a look of tremendous power.

On 14th June 1930 the EMPRESS OF JAPAN left Liverpool on her maiden voyage to Quebec, returning to Southampton. On her return passage she averaged 21 knots on 26,100shp. Her fuel consumption was 168 tons per day. On 12th July she left Southampton for Hong Kong via Suez, and from Hong Kong commenced her trans-Pacific service to Vancouver via Shanghai, Kobe and Yokohama, joing her three running-mates, the EMPRESS OF CANADA, the EMPRESS OF ASIA and the EMPRESS OF RUSSIA.

Normally, there would have been a balancing pair of sister ships, but the world depression was affecting policy, and with the advent of its new trans-Atlantic flagship, the EMPRESS OF BRITAIN of 1931, Canadian Pacific Steamships had enough on its plate.

Along with the EMPRESS OF CANADA of 1922, the new EMPRESS OF JAPAN had sufficient speed to include a call en route at Honolulu, lengthening the passage by a considerable amount and bringing the new ship into direct competition with the American and Japanese liners on the Pacific.

The EMPRESS OF JAPAN leaving Vancouver

The EMPRESS OF JAPAN lost little time in capturing the speed record for the trans-Pacific passage in both directions. In October 1930 she averaged 21.02 knots from Yokohama to Race Rocks, Vancouver, completing the passage in 8 days, 6 hours and 27 minutes, beating the EMPRESS OF CANADA's previous record by four and a half hours. In 1931 she reduced this time to 7 days, 8 hours and 27 minutes. The largest and fastest ship on the Pacific, the EMPRESS OF JAPAN was for eight years extremely popular and before the end of 1939 she had completed 58 round voyages.

The EMPRESS OF JAPAN on trans-Pacific service.

On 26th November 1939 the EMPRESS OF JAPAN was requisitioned as a troopship. She had been in Shanghai when war was declared and after a crossing to Honolulu and Vancouver, she sailed for Esquimalt where a certain amount of work was carried out to fit her for trooping. Her hull and superstructure were painted grey and she then left for Sydney, arriving on 22nd December.

Shortly afterwards she sailed for Suez with a contingent of Australian troops. Returning to Melbourne, she sailed again with troops to Suez in the company of the QUEEN MARY, AQUITANIA, MAURETANIA, EMPRESS OF BRITAIN and the EMPRESS OF CANADA. In 1941 the EMPRESS OF JAPAN completed trooping voyages from Glasgow to the Cape and Singapore, returning to the UK via Panama: 35,000 miles in 141 days.

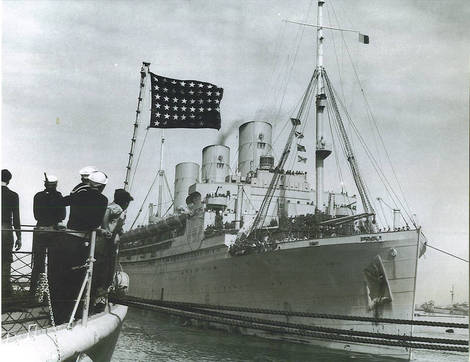

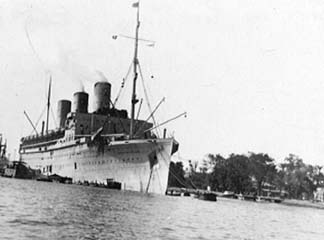

The EMPRESS OF JAPAN (by now renamed EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND) as a troopship in the Second World War.

Following the entry of Japan into the Second World War, the EMPRESS OF JAPAN was renamed EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND, ten months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. At this time changes of ships' names were prohibited, but Winston Churchill said that in the case of the EMPRESS OF JAPAN "It is a nonsense", and so on 16th October 1942 she became the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND, the second of that name in the Canadian Pacific fleet, the first having been the ex- KAISERIN AUGUSTE VICTORIA in 1921.

In 1942, under heavy air attack, the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND took 1,700 women and children away from Singapore to Colombo. During 1943/1944 she was on trooping service from Halifax, N.S., New York and Newport News to Liverpool and to Casablanca, carrying a total of 30,000 American troops.

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND at Suez

On 9th November 1944 the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND was subject to an air attack off Northern Ireland; three bombs being such near misses that they actually glanced off the ship's rails and a lifeboat, exploding in the sea. Captain J.W. Thomas had given evasive-action orders to the quartermaster who swung the wheel whilst lying on his stomach to avoid machine gun bullets which were raking the bridge! Both men were later decorated for their bravery.

Following the cessation of hostilities the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND continued trooping, repatriating troops and their families until she was released at Liverpool on 3rd May 1948. During the years 1939/1948, the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND had steamed three times round the world, twice westbound and once eastbound; had sailed five times to South Africa and Singapore; and visited Australia and New Zealand five times. She had called at Canadian and U.S. ports on twelve occasions; sailed eight times to India; and post-war twice to Japan. In all the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND had steamed 713,000 miles on war service and had carried 292,000 troops as well as other passengers.

When released the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND was the only 'Empress' left in the Canadian Pacific fleet. The EMPRESS OF RUSSIA had been burnt out at Barrow-in-Furness in 1945 whilst refitting. The EMPRESS OF ASIA was sunk in 1942 off Singapore by Japanese aircraft. The EMPRESS OF CANADA had been torpedoed and sunk in the South Atlantic when homeward bound from Durban, and the EMPRESS OF BRITAIN, completed in 1931, was set on fire by air attack in October 1940, and subsequently torpedoed whilst under tow. The EMPRESS OF AUSTRALIA remained a troopship until sold to breakers in 1952 and was never returned to Canadian Pacific.

Of the four 'Duchesses' completed in 1928/29, only two remained after the war; the DUCHESS OF BEDFORD and the DUCHESS OF RICHMOND. In 1947 these two ships were elevated to 'Empresses' with white hulls and green ribands and renamed respectively EMPRESS OF FRANCE and EMPRESS OF CANADA. Given this state of affairs, Canadian Pacific abandoned its Far East - Vancouver service and accordingly the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND was refitted for the North Atlantic.

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND as she appeared on her re-entry into passenger service on the North Atlantic in May 1950.

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND was sent back to her builders, the Fairfield Yard at Govan, for a full refit for the Liverpool - Quebec mail service, and also for winter cruising. After eight years as a troopship, this was a job which took from June 1948 until May 1950.

The passenger accommodation was completely transformed. No space was now needed for Asiatic steerage passengers and this enabled very great improvements to be made to the crew accommodation. The ship was refitted for 458 first-class passengers and 205 in tourist class. All deck coverings had to be renewed and the promenade deck was glassed-in for its whole length, this being more appropriate for typical North Atlantic conditions.

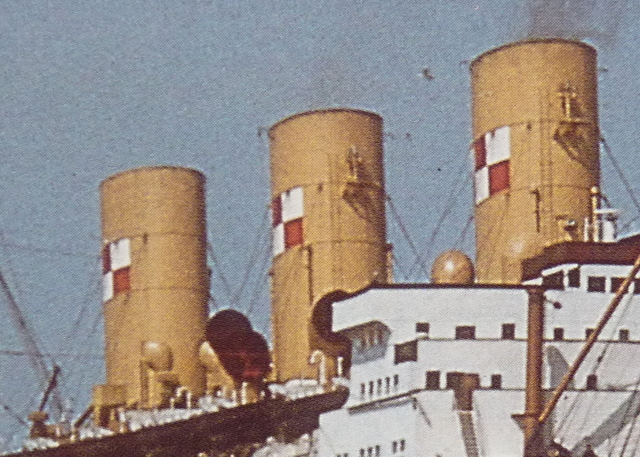

Externally the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND was repainted with a white hull and yellow funnels, but the previous blue riband of the 1930s was changed to green, and the company's red and white chequered houseflag was painted on all three funnels. The propelling machinery remained the same but was given a complete overhaul and new propellers were fitted. On trials over the Arran Mile, after the completion of the refit, she reached a very creditable 22.5 knots.

The first-class cocktail bar in the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

The swimming pool in the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

The first-class main lounge in the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

The first-class main entrance in the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

The first-class restaurant in the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

The first-class writing room and library in the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

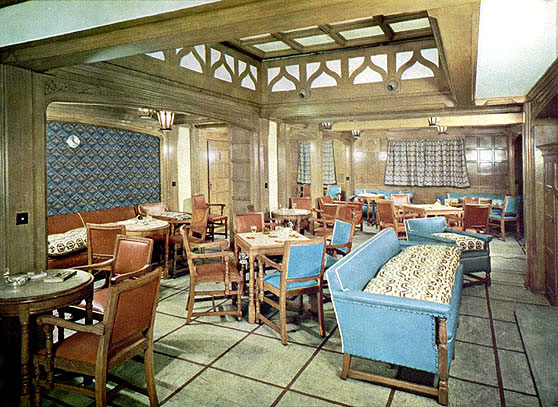

The tourist-class smokeroom on the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

The tourist-class restaurant on the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

The tourist-class lounge on the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

The first-class card room on the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

A tourist-class three-berth stateroom on the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

A first-class stateroom on the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

A group of the stewards employed in the first-class dining saloon on the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND in 1952.

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND left Liverpool on 9th May 1950 on her first post-war commercial voyage to Quebec, with a call at Greenock. She was the only Empress to make the Scottish call until the advent of the new ships in the mid 1950s. On her second eastbound crossing she broke the record for the St Lawrence - Clyde passage by seven hours, with a passage time from the pilot station at Father Point in the Gulf of St Lawrence to the Clyde pilot station off the island of Little Cumbrae of five days and forty-two minutes at an average speed of 21.3 knots.

At the Tail of the Bank, Greenock Passing Quebec, outward bound

In mid-Atlantic Liverpool's only three-funnelled liner

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND bettered these passage times later in the summer of 1950 by using the Belle Isle Strait (between the northern tip pf Newfoundland and the south of Labrador), rather than sailing south-about Newfoundland via Cape Race. This route cut the distance from 2,728 miles to 2,558 miles, and the Empress crossed from the Clyde Pilot to Father Point in four days, fourteen hours and forty-three minutes, at an average speed of 21 knots.

"Will Ye No Come Back Again ..... ?" The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND was the only Canadian Pacific liner to include the Greenock call in her schedule until the new ships entered service in the mid 1950s. It was a tradition for a Scottish piper to play a lament just before the ship sailed for Canada.

A busy scene at the Tail of the Bank off Greenock, with the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND making her call en route from Liverpool to Quebec and Montreal

Cruising in the winter months became a regular part of the schedule and in December 1950 the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND made her first cruise from New York to the West Indies, resuming Canadian Pacific's pre-war crusing programme. A 17-ton swimming pool was hoisted on board for the benefit of cruise passengers.

THE ROYAL VOYAGE

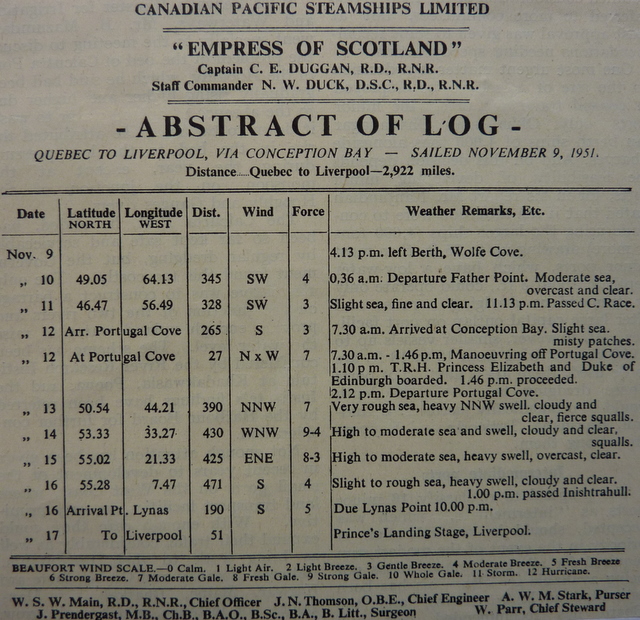

In November 1951, Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh returned from their Canadian tour on the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND. The Empress had left Quebec at 4.13pm on 9th November and arrived off Portugal Cove in Conception Bay, Newfoundland, at 7.30am on 12th November.

The Senior Officers on the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND for the 'Royal Voyage'. Left to Right: Mr Jan Bezant, First Officer; Staff Commander N.W. Duck, Captain C.E. Duggan, and Chief Officer Mr W.S. Main.

There was a north-easterly gale blowing, as a result of which the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND was unable to anchor and was skilfully manoeuvred by Captain C.E. Duggan whilst constantly being driven towards the shore.

The royal couple had a rough one-and-a-half mile passage out to the Empress on board the 140-ton ferry MANECO which took forty-five minutes. Photographers and officials on two fishing trawlers which accompanied the MANECO were soaked to the skin! The MANECO was alongside the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND at 1.10pm, and after the royal couple had boarded and their entire baggage had been transferred, the Empress sailed at 1.46pm.

Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh occupied the main suite on 'A' deck which had been partitioned off under constant guard by selected stewards to ensure privacy. It was hardly necessary, however, for the word had been passed round tactfully amongst the other passengers during the two-day passage from Quebec and around to Conception Bay that the Princess and the Duke would like to relax and enjoy themselves as ordinary passengers. And so it was.

Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh on board the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

Captain Duggan introduces Princess Elizabeth to members of the crew of the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

For about forty miles out from Conception Bay, the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND was escorted by HMCS ONTARIO and the destroyer MICMAC, and it was planned that they would 'man ship' to give the traditional naval farewell, but in the prevailing heavy seas this was abandoned as being too dangerous. The destroyers HMS ZAMBESI and HMS CREOLE met the Empress off the Ulster coast to escort her into the Mersey, but they too were forced to break station because of bad weather in the confined shipping lanes of the Irish Sea.

Abstract of Log for the 'Royal Voyage' on the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND arrived alongside Princes Landing Stage at Liverpool at 6.am on 17th November 1951, where the Royal couple disembarked.

______________________________________________

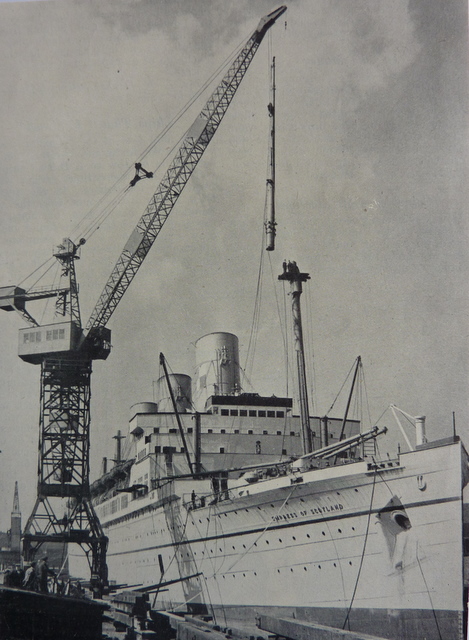

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND in the Canada Dry Dock, Liverpool, having her masts shortened in April, 1952.

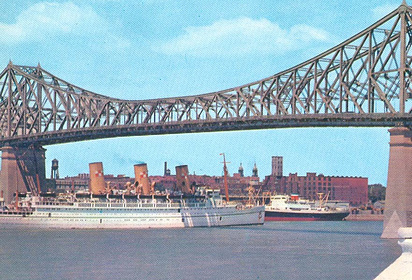

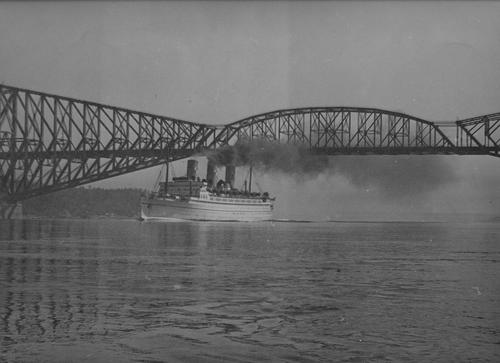

In April 1952 the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND's masts were shortened by 44 feet to allow her proceed up the St Lawrence to Montreal, necessitating passing under both the Quebec Bridge (about five miles upstream from Quebec City), and the Jacques Cartier Bridge at Montreal. The channel to Montreal had by this time been deepened and the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND became the largest vessel ever to dock in Montreal.

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND passing under the Jacques Cartier Bridge on departure from Montreal.

In April 1956 the new EMPRESS OF BRITAIN entered service, followed a year later by the EMPRESS OF ENGLAND. With the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND and the EMPRESS OF FRANCE, there were again four Empresses on North Atlantic service. With the new EMPRESS OF CANADA shortly to join the fleet, these newcomers spelt the end for the two older ships. The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND was sold first, and the EMPRESS OF FRANCE went to the breakers in 1960.

On 8th November the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND left Liverpool on her final voyage for Canadian Pacific. She arrived back in Liverpool for the last time in a chill wintry mist on 26th November 1957 under the command of Captain S.W. Keay, and after disembarking her 213 passengers at Princes Landing Stage, she was laid up in the Gladstone Dock.

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND being assisted on to her berth at Princes Landing Stage by the Alexandra tugs EGERTON (forward) and ALFRED (aft).

Captain Keay was interviewed by a reporter from the Liverpool Echo and commented: "Occasions such as these are always sad. Members of the crew have been sailing on this route for many years, and everyone is feeling the parting very much today." There was a farewell party on board on the last night of the voyage and a member of the crew said: "It was the quietest party I have ever seen on a ship. Everyone seemed to be too sad to make merry."

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND alongside Princes Landing Stage, Liverpool, ready to sail on yet another voyage to Canada.

For three members of the crew, the occasion was a doubly poignant one. As well as parting from the Empress, they were also finishing their seafaring life. The three men were William Campbell, First Radio Officer; John Butterworth, Second Radio Officer; and William Lambard, the ship's dispenser. Mr Campbell had been at sea with Canadian Pacific since 1922, and Mr Butterworth was retiring after forty-five years at sea. Mr Lambard was the first dispenser ever to be appointed by Canadian Pacific, and after completing thirty-seven years he commented: "There is no life like one at sea. It has gone like a flash, and I can hardly realise that it is time for me to retire. I am glad that I am going at the same time as the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND. She has been a grand ship to sail on."

Just before the New Year the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND was sold to the Hamburg-Atlantic Line and left Liverpool on 31st December 1957 for Belfast. Following a dry-docking and survey, she was accepted by her new owners and was handed over to them at Belfast on 17th January 1958.

On 19th January 1958 the old ship left Belfast under the German flag and with the temporary name of SCOTLAND. Two days later she arrived at the Howaldtswerke Company's yard at Hamburg. Here she was renamed HANSEATIC and reconstructed and 'modernised' during a six-month overhaul which cost 43 million Deutschmarks.

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND approaching her anchorage at the Tail of the Bank, off Greenock, in the Firth of Clyde

The Hamburg-Atlantic Line was a final atempt to operate a trans-Atlantic passenger service from Hamburg after HAPAG had given up passenger carrying. With the growth of the post-war German merchant fleet it was strongly felt during the mid 1950s that the time was ripe for Germany to re-enter the traditional trans-Atlantic passenger service with a Hamburg-owned liner. In 1957 the Hamburg-Atlantic Line G.m.b.H. was formed. A decision was made to start with a second-hand vessel and shortly afterwards the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND appeared on the market for sale.

The old EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND was given a new, slightly raked, bow during her conversion to the HANSEATIC.

The funnel colours of the HANSEATIC were red with a black top and a white logo in the red sector. The hull was painted black. The passenger accommodation was rebuilt to carry 85 first-class and 1,165 tourist-class passengers. The third funnel was removed and replaced by two shorter and more 'modern' ones. For some reason it was thought worthwhile to alter her bow, giving it a slightly raked curve at the top, which increased the overall length by about six feet.

The HANSEATIC arriving at New York on her maiden voyage for the Hamburg-Atlantic Line

The rebuilding took about six months and on 21st July 1958 the HANSEATIC left Cuxhaven for New York via Le Havre, Southampton and Cobh. In 1959 the ship made twelve round trans-Atlantic voyages and went cruising in the winter months. By 1965 competition from the airlines meant that the New York voyages were reduced to eight and the HANSEATIC spent most of her time cruising.

The HANSEATIC sailing from New York. Note the funnel uptakes, fitted to reduce the smoke nuisance.

On 7th September 1966, whilst lying at New York, fire broke out in the HANSEATIC's generator room, caused by oil leaking from a fractured pipe line. It took 200 firemen to bring the blaze under control, by which time great damage had been done. Not only had the generators been ruined, but the engine room had suffered considerably from the intense heat and the water, while smoke and water had caused damage to much of the passenger accommodation. The HANSEATIC's passengers were transferred to the QUEEN MARY, whose sailing time was delayed by some four hours while they were transferred.

The HANSEATIC (ex EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND) resplendent in the colours of the Hamburg-Atlantic Line

The HANSEATIC was towed to Todd's shipyard at Brooklyn for survey, and as a result Hamburg-Atlantic decided to have her towed back to the Howaldtswerke yard at Hamburg for possible repair. On 3rd October 1966 the HANSEATIC left New York for the 17-day tow by two tugs to Hamburg where the damage was found to be too severe to be worth repairing. The ship was sold for scrap on 2nd December 1966 to Elkhart & Company for 15 million Deutschmarks. Such, then, was the sad end of the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND. _______________________________________________________________

WESTERN OCEAN INTERLUDE

by Captain Brian Scott

At the end of my four-year cadetship with the Clan Line in 1956, I wanted to attend Liverpool Technical College to obtain my first certificate, However, my timing was wrong - the College was due to close for the summer holidays. Remembering what a third mate had told me about his experience of being seconded to Canadian Pacific Steamships as an uncertificated fifth officer, I decided to follow suit.

I joined the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND at Liverpool in June 1956, put on my boiler suit, and as junior cargo officer on six-hour port watches, did exactly the same as when I was a cadet. Cargo work was hectic on the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND due to the quick turnround. There was tank cleaning after discharging tallow, hold cleaning after grain, plus the requirement to work out the vessel's stability morning and evening due to ballasting/deballasting, refuelling and taking on fresh water. Outward cargo consisted of high value goods such as mails, crockery, textiles, woollen goods, motor cars and machinery.

When sailing day arrived it was no watch below and no rest as the second mate and myself had amended the crew boat and fire station lists during the previous night, and then the M.O.T. surveyor was present for the crew boat drill. We next moved from Gladstone Dock to Liverpool Landing Stage with the company pilot and five tugs. Gangway duty was tourist class for the fifth officer and first class for the fourth officer. Then we were on our way, calling at Greenock where we disembarked the Liverpool Pilot, embarked more passengers, lowered all lifeboats into the water and took some of them for a run around the anchored ship.

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND passing under the Quebec Bridge on passage from Quebec to Montreal

The centre span of the Quebec Bridge being hoisted into position in September 1916

On arriving and sailing, my station was on the bridge with the Captain, Staff Captain and Second Officer, who was my senior on the 12 to 4 watch at sea. This was not a problem for me as for part of my cadetship I had been bridge cadet for arrivals and departures. When no fourth officer had been carried on my Clan Line voyages, I was frequently on watch with the chief officer on his 4 to 8 watch.

After leaving Greenock we settled into our watchkeeping routine. The first (navigator) and fourth officers on the 4 to 8; the second and fifth on the 12 to 4, and the third officer (who held a master's certifcate) on the 8 to 12, with the day worker chief officer on stand-by to go on the bridge if the weather or visibility became poor. The captain and staff captain always appeared to be busy with other heads of departments, and the four radio officers laboured away with high speed Morse messages for the ship's daily newspaper, ice reports, and six-hourly weather reports to shore stations.

My days and nights were busy. Before each bridge watch I mustered my deck watch at the emergency boat (No.1 or No.2). After each watch we held fire drill and each day I went along a different deck with my plug-in telephone testing the fire alarms. This ensured that junior officers knew every nook and cranny on board. The fourth officer was the met. officer and had plenty to keep him busy as well as the boat drills. Life was well ordered.

The watchkeeping officers dined in an alcove in the first-class dining saloon. However, being on the 12 to 4, I had 'brunch' brought to my cabin at 10.am, skipped lunch and had dinner at 6.30pm. In between times there was always plenty of tea, coffee and sandwiches available on the bridge. Sometimes the quartermasters got the lion's share of the sandwiches !

On my two voyages on the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND the weather was fine, a little ice, but quite a lot of cargo ship traffic. Passenger ships stuck to the Atlantic routing / separation lanes of longstanding to avoid head-on situations with each other, as at 22 knots the closing speed was quite intimidating. As a safety measure, at the start of each watch, a notebook with the vessel's dead-reckoning positions for the next four hours, complete with local and GMT, was handed to the duty radio officer.

The EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND alongside at Wolfe's Cove, Quebec

We stopped at Quebec to disembark some passengers and then proceeded to Montreal where the remainder left. We discharged cargo, had more boat drills, and then loaded grain, sawn timber, apples, bulk tallow, mail and gold and silver bullion for Liverpool. The passengers boarded and we sailed for Quebec and Liverpool.

On completion of my two relief voyages, the regular fifth officer returned from leave. For my part, I had learned a lot with regard to shipboard organisation, the routine of ocean navigation on fast ships, the use of Loran, ice and weather reports, plotting of such information on special charts, and practical ship stability. The experience paid dividends, for some years later I wanted a summer fill-in job prior to attending nautical school, and was fortunate enough to be appointed as relief fourth officer on both of the new sister ships EMPRESS OF BRITAIN and EMPRESS OF ENGLAND.

__________________________________________

________________________________________

|